By the late 1950s, Brazilian cinema wasn’t just behind Hollywood-it was barely visible. Most films were lightweight musicals, romantic comedies, or cheap imitations of American B-movies. Then, in 1960, everything changed. A group of young filmmakers, armed with 16mm cameras, radical ideas, and a hunger for truth, launched Cinema Novo. They didn’t want to entertain. They wanted to expose. To shake the country awake.

The Birth of Cinema Novo

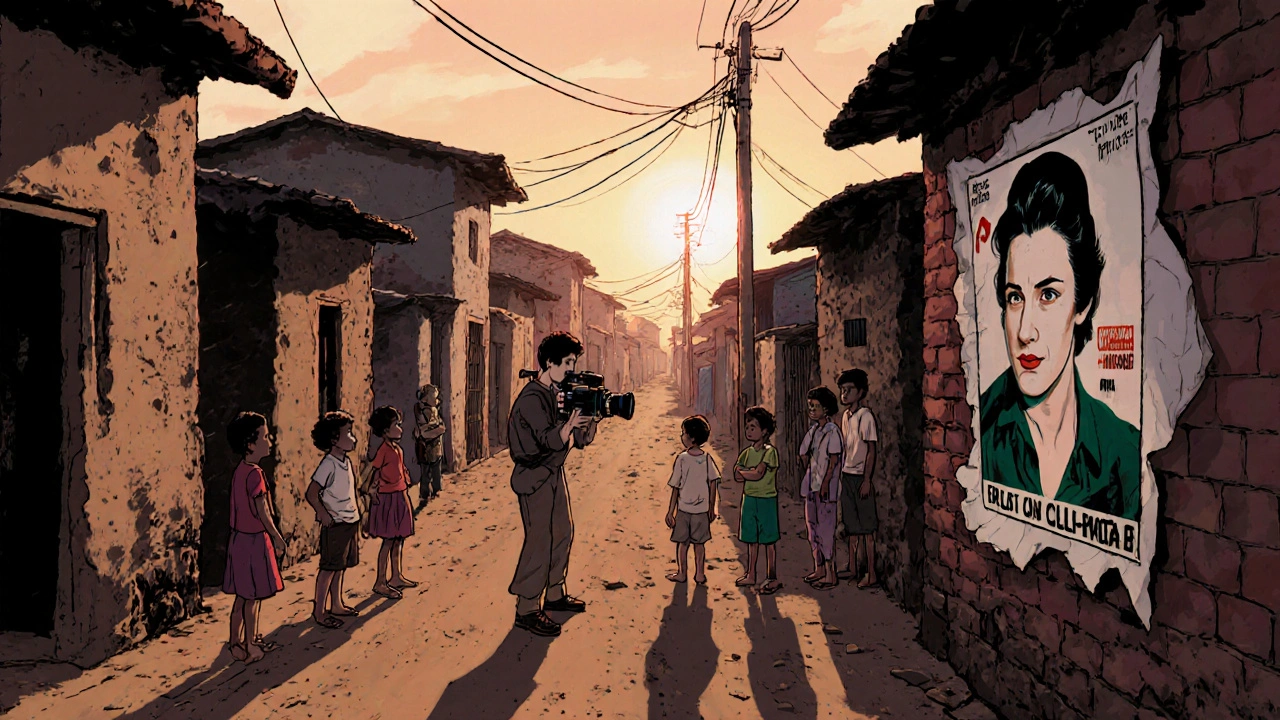

Cinema Novo wasn’t just a film movement. It was a revolution wrapped in celluloid. Led by Glauber Rocha, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, and Carlos Diegues, these filmmakers rejected polished studio productions. They shot on location-in favelas, on dusty highways, in remote northeastern villages. Their cameras didn’t hide poverty; they stared it down.

They borrowed from Italian Neorealism but added something uniquely Brazilian: a raw, poetic anger. Rocha’s Black God, White Devil (1964) didn’t just show a peasant’s struggle-it made the struggle feel like a myth. The land was cursed. The church was corrupt. The state was absent. The hero wasn’t a hero-he was a survivor, bleeding and confused.

These films had no budget for lighting rigs or sound stages. They used natural light. They recorded dialogue with handheld mics. They cast non-professionals: farmers, street kids, laborers. That wasn’t a limitation. It was the point. Reality wasn’t something to be staged. It was something to be lived.

Political Fire and Censorship

Cinema Novo didn’t just reflect Brazil’s inequality-it blamed it. The government didn’t like that. By the mid-1960s, after the military coup in 1964, censorship tightened. Films were banned. Prints were seized. Filmmakers were arrested. Rocha was exiled. Dos Santos was forced to tone down his messages.

But the movement didn’t die. It adapted. Filmmakers turned to allegory. Symbols replaced direct criticism. A broken tractor became the broken promise of progress. A child’s empty bowl became the silence of the poor. Even under repression, the camera kept rolling.

One of the most powerful films of this era was Vidas Secas (1963), directed by Nelson Pereira dos Santos. Based on Graciliano Ramos’s novel, it followed a poor family drifting through the drought-stricken sertão. No music swelled. No dialogue explained. Just silence, dust, and hunger. The film won awards in Europe. Back home, it was called dangerous. It was also unforgettable.

The Shift: From Revolution to Reflection

By the 1980s, the military dictatorship was crumbling. Brazil was opening up. Cinema Novo’s fiery urgency began to fade. A new generation emerged-not to overthrow the state, but to understand it. The anger didn’t disappear. It matured.

Directors like Walter Salles and Cao Hamburger started telling stories not of revolution, but of aftermath. Central Station (1998), directed by Salles, followed an aging woman who writes letters for illiterate travelers-and then kidnaps a boy to sell him. It sounds dark. But the film isn’t about evil. It’s about connection. About how broken people find each other in a broken system.

There were no revolutionaries here. No armed peasants. No poetic monologues about imperialism. Just a bus ride through Brazil’s heartland, two lonely souls, and a quiet, devastating hope.

The Rise of Contemporary Social Drama

Today, Brazilian cinema is more diverse than ever. But its soul still echoes Cinema Novo: truth over glamour, the marginalized over the powerful.

City of God (2002), directed by Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund, didn’t glamorize gang life. It showed how poverty, neglect, and police violence turn children into killers. The film used real favela kids as actors. Some had never seen a movie before. One of them, Alice Braga, became an international star. Others? They disappeared back into the system.

Then came Neighboring Sounds (2012) by Kleber Mendonça Filho. A quiet, slow-burning thriller set in a middle-class neighborhood. No explosions. No guns. Just the sound of a dog barking, a neighbor’s TV, and the creeping dread of class tension. It’s a film about how privilege hides in plain sight.

And in 2021, Bacurau by Juliano Dornelles and Kleber Mendonça Filho turned social critique into a genre-bending nightmare. A remote village in the Brazilian interior vanishes from maps. Then strangers arrive. And the villagers start fighting back-with shotguns, old radios, and ancient traditions. It’s a horror film. A western. A political manifesto. And it won the Jury Prize at Cannes.

Themes That Never Fade

What ties Cinema Novo to today’s Brazilian dramas? Three things:

- Class as character: The rich aren’t villains. They’re invisible. They’re the ones who never show up on screen-but their absence shapes every frame.

- Place as prison: Whether it’s the sertão, the favela, or the gated community, geography determines fate.

- Silence as speech: The most powerful moments are often wordless. A glance. A hand reaching out. A child staring into the camera.

Even when budgets grow and technology improves, Brazilian filmmakers still avoid Hollywood-style resolutions. Happy endings are rare. Justice is uneven. Survival is the only victory.

Why It Matters Beyond Brazil

Brazilian cinema doesn’t just tell stories about Brazil. It shows how global systems-colonialism, capitalism, inequality-play out in real lives. It’s not about exoticism. It’s about recognition.

When you watch Central Station, you’re not watching a Brazilian film. You’re watching a story about what happens when the system forgets people. That’s not unique to Brazil. It’s happening everywhere.

That’s why these films travel. Why they win awards in Berlin, Toronto, and Cannes. Why students in Tokyo and Berlin study them. Because they prove cinema doesn’t need big stars or CGI to be powerful. It just needs truth.

Where to Start Watching

If you’re new to Brazilian cinema, here’s a roadmap:

- Vidas Secas (1963) - The quiet horror of poverty.

- Black God, White Devil (1964) - The mythic rage of Cinema Novo.

- Central Station (1998) - The emotional bridge between eras.

- City of God (2002) - The raw energy of urban survival.

- Bacurau (2019) - The modern, genre-bending protest.

Watch them in order. You’ll see how a country’s cinema evolved-not from style, but from struggle.

What is Cinema Novo?

Cinema Novo was a Brazilian film movement that began in the late 1950s and peaked in the 1960s. It rejected commercial, studio-made films in favor of low-budget, location-shot stories focused on poverty, inequality, and political oppression. Key figures include Glauber Rocha, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, and Carlos Diegues. The movement used non-professional actors, natural lighting, and social realism to challenge Brazil’s elite narratives.

Is Brazilian cinema still politically charged today?

Yes. While modern Brazilian films don’t always use the same revolutionary language as Cinema Novo, they still confront deep social issues: racism, police violence, land inequality, and corruption. Films like Bacurau and Neighboring Sounds use suspense, genre, and subtle symbolism to critique power structures. The tools changed, but the mission didn’t.

Why are so many Brazilian films set in poor areas?

Because those are the places where Brazil’s contradictions are most visible. The gap between rich and poor, between city and countryside, between law and survival, is widest there. Filmmakers don’t choose poor settings for drama-they choose them because that’s where reality lives. It’s not about pity. It’s about witness.

Who are the most important directors in Brazilian cinema today?

Kleber Mendonça Filho, Juliano Dornelles, Walter Salles, and Anna Muylaert are among the most influential. Mendonça Filho and Dornelles brought international attention with Bacurau. Salles shaped global perceptions with Central Station and The Road. Muylaert’s The Second Mother explores class through domestic labor with quiet precision.

How did Cinema Novo influence global cinema?

Cinema Novo inspired movements like Third Cinema in Latin America and the New Nigerian Cinema. Its focus on grassroots storytelling, anti-colonial themes, and low-budget realism influenced filmmakers from Iran to South Africa. Directors like Ken Loach and the Dardenne brothers have cited it as an influence. It proved you didn’t need Hollywood money to make urgent, lasting art.