The jungle didn’t care about the dream

Werner Herzog wanted to haul a 320-ton steamship over a mountain in the Peruvian rainforest. Not with CGI. Not with models. Not with tricks. He wanted to do it for real-using ropes, manpower, and sheer will. The result was Fitzcarraldo, a film that became legend. But the real masterpiece wasn’t the movie Herzog made. It was the documentary that watched him try-and fail-and try again. Burden of Dreams didn’t just record the chaos. It turned it into cinema.

What happened when the dream turned into a nightmare

In 1979, Herzog’s production of Fitzcarraldo collapsed. Jason Robards, cast as the lead, got sick. Mick Jagger dropped out. The money vanished. Instead of walking away, Herzog doubled down. He recast the film with Klaus Kinski-the actor he called his “best fiend”-and began again. This time, there was no studio safety net. No insurance. No backup plan. Just a crew, a steamship, and 700 indigenous Aguaruna laborers.

They cleared 1,500 meters of jungle. They carved a 30-meter-wide trench through primary rainforest. They dragged the ship up a 40-meter slope using nothing but pulleys, ropes, and human strength. The jungle fought back. Rain flooded the site. Equipment rusted. Workers walked off. Herzog’s temper grew wilder. At one point, he told his crew: “I don’t think the birds sing. They just screech in pain.”

But while Herzog saw the jungle as an enemy to be conquered, Les Blank saw something else.

Les Blank’s camera didn’t follow the director-it watched the world

Blank wasn’t there to make a making-of documentary. He was there to make a film about obsession. And he did it with a handheld 16mm camera, minimal gear, and no script. His crew worked in 90% humidity, 38°C heat, and constant insect swarms. They didn’t have the budget for fancy equipment. They didn’t need it.

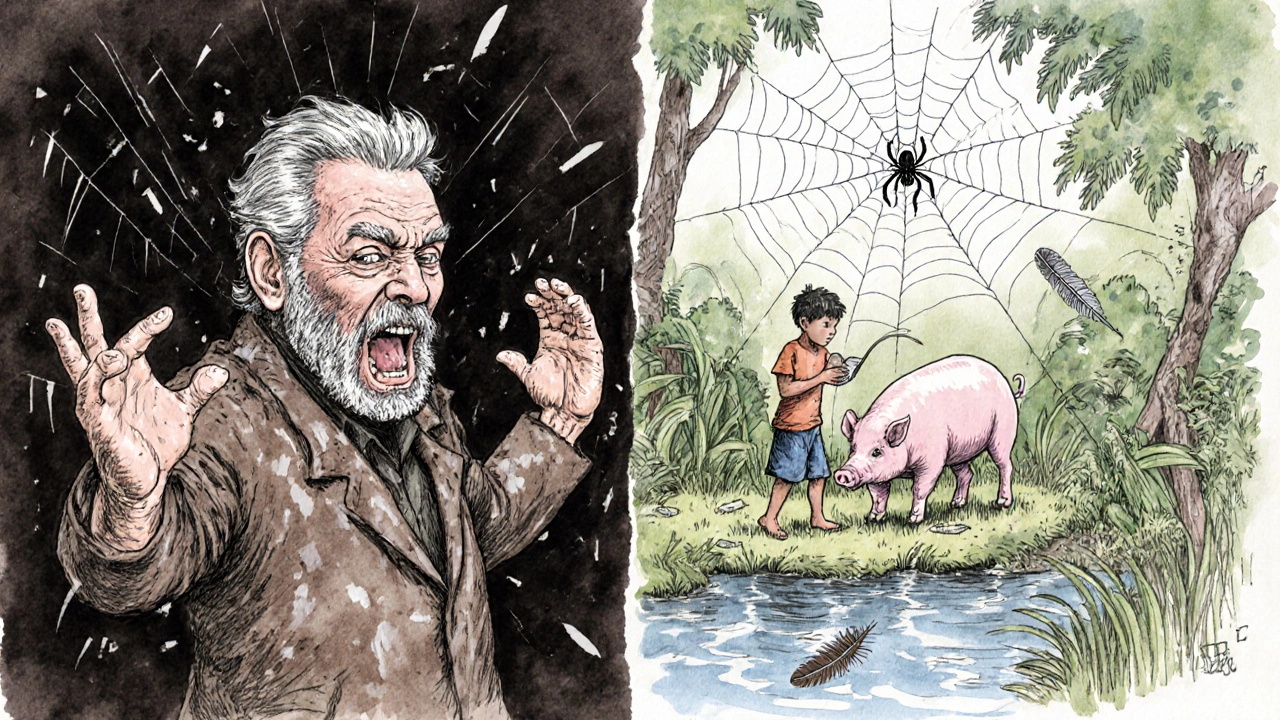

Blank’s cinematography was quiet. Patient. Observational. He didn’t chase Herzog. He waited. He filmed the ants crawling beneath a red feather after Herzog spoke about nature’s “murderous harmony.” He filmed the Aguaruna men staring into the lens after presenting a parrot’s corpse-a silent, powerful rebuke to the madness unfolding around them. He filmed the steamship slipping backward down the slope, the ropes snapping, the men shouting, the jungle swallowing the chaos.

Where Herzog’s camera framed his ship as a symbol of human triumph, Blank’s camera showed the jungle breathing around it. Trees regrew where bulldozers had cut. Birds returned after the noise faded. Life kept going. The film didn’t take sides. It just showed both.

The editing that made the documentary unforgettable

Maureen Gosling’s editing is what turned raw footage into poetry. She didn’t cut Herzog’s monologues short. She let them hang in the air-then cut to a spider spinning its web, a child laughing in the river, a parrot flying free. The contrast wasn’t accidental. It was intentional.

One moment, Herzog says: “I live my life, I end my life with this project.” The next shot: an indigenous boy feeding a pig. No music. No narration. Just silence and movement. That’s the heart of Burden of Dreams. It doesn’t explain Herzog. It doesn’t judge him. It just lets the world respond.

There’s a scene where an actor, exhausted and covered in mud, looks into the camera and says: “Acting gives me physical pleasure. Otherwise, I’d be a bank manager.” It’s not profound. It’s not poetic. It’s human. And that’s why it sticks. Blank didn’t stage it. He didn’t ask for it. He just kept rolling.

Why this documentary changed filmmaking forever

In 1982, no one made documentaries like this. Studios didn’t allow access. Directors didn’t want their failures shown. Herzog did. He gave Blank full access. That kind of trust is rare. And Blank didn’t waste it.

Burden of Dreams became the blueprint for every film about filmmaking that came after. Hearts of Darkness (1991), about the making of Apocalypse Now, borrowed its structure. Lost in La Mancha (2002), about Terry Gilliam’s failed Don Quixote, copied its tone. But none matched its depth.

Why? Because Blank didn’t make a film about a mad genius. He made a film about the cost of obsession. He showed the laborers who carried the ship. He showed the trees that fell. He showed the birds that kept screeching. He showed the jungle that didn’t care if Herzog succeeded or failed.

It’s not a behind-the-scenes look. It’s a mirror. And it reflects something uncomfortable: that the most powerful art often comes at the expense of everything else.

The 2023 restoration: why it matters now

In 2023, a 4K remaster of Burden of Dreams was released. Harrod Blank, Les’s son, and sound engineer William Blick worked with the original Nagra audio tapes-recorded on location in the jungle over 40 years ago. They fixed the sound. They sharpened the image. They brought the jungle back to life.

For the first time, audiences could hear the rain clearly. The rustle of leaves. The distant call of howler monkeys. The creak of ropes under strain. The sound design wasn’t just restored-it was resurrected.

That’s why this film matters today. We live in an age of digital perfection. We edit out mistakes. We delete failures. We polish every frame until it’s sterile. Burden of Dreams reminds us that the real magic isn’t in the final product. It’s in the mess. In the sweat. In the silence between the words.

What filmmakers can learn from this

- Access beats control: Herzog gave Blank freedom. That’s why the film feels real. Most directors would have locked the camera out.

- Observation > narration: Blank didn’t explain Herzog. He let the images speak. That’s harder, but more powerful.

- Constraints spark creativity: With no budget, Blank used what he had. That’s why the handheld shots feel alive.

- Let the environment respond: The jungle wasn’t a backdrop. It was a character. The best documentaries don’t just film people-they film the world around them.

Herzog wanted to move a ship. Les Blank moved something deeper: how we think about art, sacrifice, and the price of obsession.

It’s not about the ship. It’s about what it cost.

Years later, Herzog made another documentary about Klaus Kinski: My Best Fiend. It’s a portrait of a toxic genius. But in that film, the jungle is just scenery. The birds don’t screech. The ants don’t crawl. The jungle doesn’t matter.

That’s the difference.

Burden of Dreams doesn’t glorify Herzog. It doesn’t condemn him. It just shows him-and the world he broke-together. And in that balance, it became something greater than a film about a movie. It became a film about life.

Is Burden of Dreams a documentary about Fitzcarraldo?

Yes, but not in the way you think. It’s not a behind-the-scenes look at how Fitzcarraldo was made. It’s a film about obsession, nature, and the cost of artistic ambition. While it documents Herzog’s production, its real subject is the tension between human will and the natural world.

Who directed Burden of Dreams?

Les Blank directed Burden of Dreams. He was a legendary American documentary filmmaker known for his poetic, observational style. He didn’t interview subjects or explain events-he let moments unfold naturally, often contrasting human actions with the environment around them.

Why is Burden of Dreams considered a masterpiece?

Because it doesn’t take sides. It doesn’t glorify Herzog’s obsession or mock it. It shows the steamship being dragged, the jungle being destroyed, the workers’ silent resistance, and the birds still flying overhead. That balance-between destruction and life, madness and meaning-is what makes it timeless.

Was Burden of Dreams shot on the same set as Fitzcarraldo?

Yes. Les Blank’s crew filmed in the same Peruvian jungle as Herzog’s main unit, often within sight of the steamship haul. But while Herzog’s team used large cameras and lights, Blank used handheld 16mm equipment. This allowed him to move quietly, capture unplanned moments, and avoid disrupting the natural environment.

How did the 2023 restoration change the film?

The 2023 4K restoration, supervised by Harrod Blank and William Blick, used the original Nagra audio tapes to rebuild the sound mix. This brought back the jungle’s natural sounds-rain, insects, birds, distant voices-that had been lost or muffled in earlier releases. Visually, the image was sharpened, revealing textures in the jungle, sweat on skin, and the grain of the original 16mm film. It’s now the clearest, most immersive version ever released.

Is Burden of Dreams worth watching if I haven’t seen Fitzcarraldo?

Absolutely. You don’t need to have seen Fitzcarraldo to understand Burden of Dreams. In fact, many viewers find Blank’s film more powerful because it stands on its own as a meditation on obsession, nature, and human limits. The steamship is just a symbol. The real story is what happens when a man tries to conquer something that refuses to be conquered.