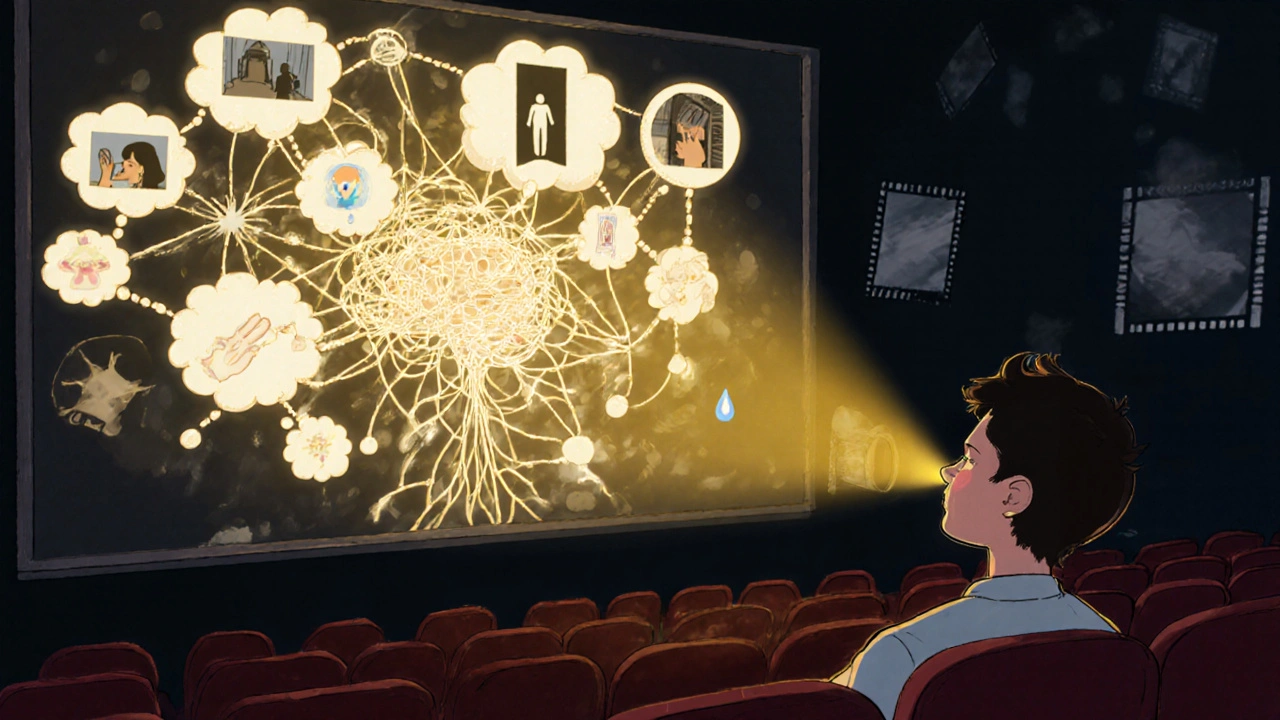

Have you ever watched a movie and felt like it was reading your mind? Not in a supernatural way - but in the way it knew exactly when to make you hold your breath, when to let you cry, or when to trick you into thinking the hero was safe? That’s not magic. It’s cognitive film theory at work.

What Cognitive Film Theory Actually Means

Cognitive film theory isn’t about decoding hidden symbols or Marxist subtext. It’s about how real human brains respond to what happens on screen. It asks: How do we follow a story when the camera cuts away? Why do we feel fear for a character we know isn’t real? How do we predict what’s coming next - and why are we sometimes wrong?

This approach, developed in the 1980s by scholars like David Bordwell and Noël Carroll, rejects the idea that film meaning is buried under layers of theory. Instead, it treats viewers as active, thinking people - not passive vessels for ideology. Your brain doesn’t need a PhD to understand a thriller. It uses the same tools it uses to navigate real life: pattern recognition, memory, expectation, and emotional calibration.

Think of it like this: When you see a character walk into a dark room, your brain doesn’t wait for a jump scare. It already assumes danger. That’s not because the film told you to feel afraid. It’s because your mind has learned, through years of experience, that darkness often hides threats. Film doesn’t create fear - it taps into it.

How We Build Stories in Our Heads

Real life doesn’t come with smooth edits or clear cause-and-effect. But films do. And your brain loves that. Cognitive theory shows we naturally fill in gaps. When a character leaves a room and reappears moments later wearing a different coat, you don’t pause to ask, "How did they change clothes so fast?" You assume time passed. You don’t question it. You narrate it.

This is called "inferential completion." It’s why montage works. In Rocky, we don’t need to see every single punch or mile run. We see a series of quick cuts: alarm clock, running through the streets, punching meat, training in the gym. Your brain stitches those images together into one continuous arc of effort. The film doesn’t show progress - your mind builds it.

Even unreliable narrators rely on this. In Shutter Island, you believe what the protagonist believes - until you don’t. The film doesn’t trick you with special effects. It tricks you because your brain is wired to trust continuity. When the same face appears in different scenes, your mind assumes it’s the same person. That’s how deception works in film: it exploits your brain’s natural tendency to simplify.

Emotion Isn’t Shown - It’s Simulated

Emotions in film aren’t delivered like a message. They’re simulated. Your brain mirrors what it sees. That’s called embodied cognition.

When you watch someone cry on screen, your own facial muscles twitch slightly. When a character runs, your leg muscles activate at a low level. This isn’t just metaphor - it’s measurable. Studies using EMG (electromyography) show viewers physically respond to on-screen movement and expression, even when they’re not consciously aware of it.

That’s why close-ups of eyes work so well. Your brain is hardwired to read micro-expressions. A slight lip tremor, a blink that’s too slow - these aren’t just acting choices. They’re emotional triggers your brain can’t ignore. Directors like Ingmar Bergman knew this. His films don’t explain grief - they show a single tear falling. And your brain fills in the rest.

Music doesn’t add emotion - it amplifies what’s already happening in your mind. A swelling string section doesn’t make you sad. It tells your brain, "This moment matters." You were already feeling it. The music just turns up the volume.

Why We Get Hooked - And Why We Get Bored

Attention in film isn’t about spectacle. It’s about curiosity gaps.

Psychologists call this the "Zeigarnik effect": unfinished tasks stick in our memory. That’s why cliffhangers work. That’s why mystery films keep us watching. The moment a character finds a hidden letter but doesn’t open it, your brain locks onto it. You won’t let go until you know what’s inside.

But here’s the flip side: if a film gives you too much too soon, you disengage. That’s why exposition dumps kill momentum. If a character says, "As you know, my father died in the war and left me this letter that contains the key to the hidden vault," your brain shuts down. It’s not because the line is bad - it’s because your brain doesn’t need to work. It’s been fed the answer before it asked the question.

Great films give you just enough to keep guessing. In Prisoners, you’re never told who the kidnapper is - but you’re given clues that feel real. You start suspecting neighbors, cops, even the victim’s father. Your brain races to connect dots. That’s engagement. That’s cognitive film theory in action.

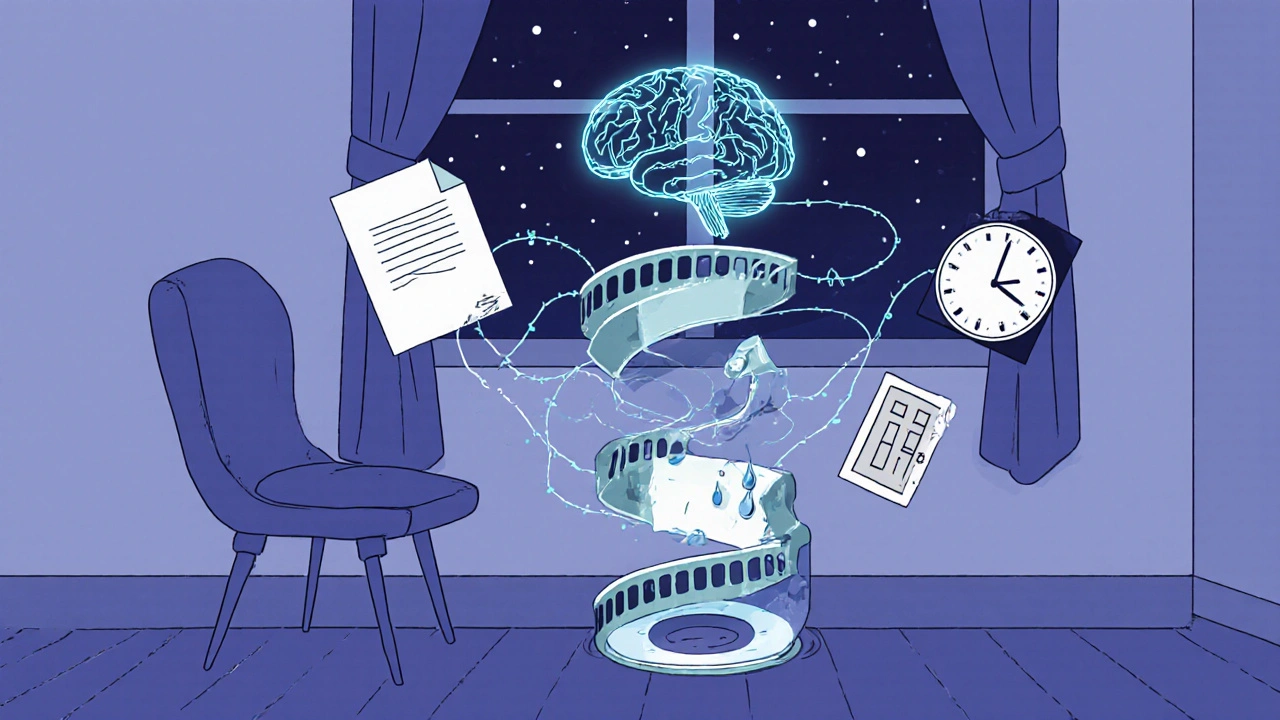

Memory, Time, and the Illusion of Continuity

Your memory doesn’t record film like a camera. It reconstructs it.

Ever watched a scene, then remembered it differently the next day? Maybe you swore the villain said "I’ll kill you" - but when you rewatched, he said, "I’ll make you suffer." That’s normal. Your brain edits films after they’re over. It smooths out inconsistencies. It removes boring bits. It adds emotional weight where it thinks it belongs.

This is why two people can watch the same movie and walk away with completely different interpretations. One remembers the romance. The other remembers the silence between scenes. Neither is wrong. They’re just remembering different versions of the same experience.

Time in film is also manipulated by your brain. A two-hour movie can feel like 40 minutes if you’re absorbed. A five-minute scene can feel like an hour if you’re anxious. That’s not editing - that’s attention. Cognitive theory shows that emotional intensity distorts perceived time. When a character is trapped in a room, every tick of the clock feels longer because your brain is hyper-focused on escape.

Why This Matters - Beyond the Theater

Cognitive film theory isn’t just for academics. It’s for anyone who watches movies - and that’s almost everyone.

Understanding how viewers process narrative and emotion helps writers craft tighter stories. It helps editors know when to cut. It helps directors choose where to place the camera. And it helps you - the viewer - understand why certain films stick with you while others vanish.

When you realize that your brain is doing most of the work, you start seeing film differently. You notice how little is actually shown - and how much is imagined. You see the artistry not in the spectacle, but in the silence between frames. In the pause before a line is spoken. In the way a character looks away instead of crying.

That’s the power of cognitive film theory: it doesn’t make movies more complex. It makes them more human.

What You Can Do With This Knowledge

Want to write better stories? Don’t explain everything. Leave gaps. Let the audience fill them.

Want to direct more emotionally powerful scenes? Focus on small details - a hand trembling, a glance that lingers. Let the camera breathe.

Want to become a sharper viewer? Pay attention to what you *don’t* see. What’s missing? What did you assume? Where did your brain fill in the blanks?

You don’t need a film degree to use this. You just need to pay attention.

Is cognitive film theory the same as psychoanalytic film theory?

No. Psychoanalytic theory, popular in the 1970s, treats viewers as unconscious subjects shaped by repressed desires and symbolic codes - often drawing from Freud and Lacan. Cognitive theory rejects that. It sees viewers as active, rational minds using everyday perception and memory to understand stories. One asks, "What does this film reveal about the unconscious?" The other asks, "How does this film work in the mind of someone watching it?"

Does cognitive film theory ignore politics or culture?

Not entirely. Cognitive theory focuses on universal mental processes - like how we recognize faces or follow cause-and-effect - which exist across cultures. But it doesn’t ignore context. Scholars like Murray Smith have shown how cultural background shapes expectations. For example, viewers from collectivist societies may interpret family dynamics in a film differently than those from individualist cultures. Cognitive theory doesn’t deny culture - it just says that culture works *through* the mind, not against it.

Can cognitive theory explain why some people cry at movies and others don’t?

Yes. Emotional responses vary based on personal experience, memory associations, and emotional sensitivity - all of which cognitive theory accounts for. Someone who lost a parent may react more strongly to a scene about grief because their brain links the film to real memories. Someone raised to suppress emotion may have a muted response, not because the film failed, but because their mind filters out the trigger. Cognitive theory doesn’t say everyone feels the same - it explains why they feel differently.

Is cognitive film theory still relevant today with streaming and short-form content?

More than ever. With binge-watching and fragmented attention spans, filmmakers must work harder to hold viewers. Cognitive principles - like curiosity gaps, emotional mirroring, and inferential completion - are now essential tools for TV writers and YouTube creators. Netflix shows like Stranger Things use slow reveals and character-driven tension because they know your brain will keep watching if it’s solving a puzzle. Short-form content survives by triggering quick emotional responses - exactly what cognitive theory predicts.

What films best demonstrate cognitive film theory in action?

Christopher Nolan’s Memento plays with memory and narrative order, forcing your brain to reconstruct time. Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men uses long, unbroken shots to make you feel trapped in the moment. Greta Gerwig’s Little Women jumps between timelines, trusting your brain to connect emotional threads without exposition. Even Pixar’s Up tells a devastating love story in five minutes - no dialogue needed. These films don’t explain. They invite your mind to participate.

Final Thought: The Real Magic Is in Your Mind

The most powerful scenes in cinema aren’t the ones with explosions or special effects. They’re the ones where nothing happens - and yet everything changes.

A mother looks at her child and says nothing. A soldier stares at a photo and turns away. A man walks out of a room and doesn’t look back.

That’s when the real work begins. Not on screen. In you.