By the late 1980s, if you walked into any video rental shop in Dublin, Tokyo, or Los Angeles, there was one shelf that always drew a crowd: Hong Kong action movies. Not the slow-burn dramas or romantic comedies. Not the kung fu flicks from the 70s. These were the films where bullets flew like rain, chairs became weapons, and a man in a trench coat would casually reload his pistol while standing on a table made of broken glass. This was Hong Kong action cinema at its peak - raw, inventive, and utterly unforgettable.

John Woo: The Godfather of Gun-Fu

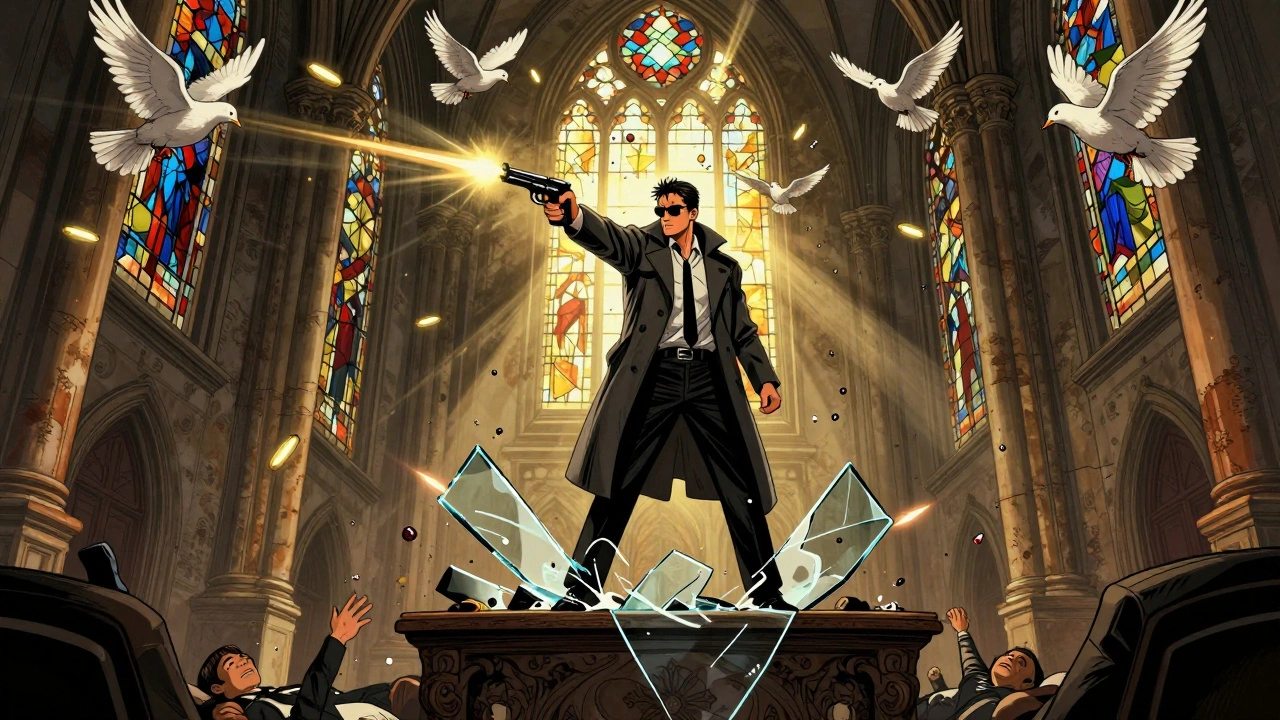

John Woo didn’t just make action movies. He turned violence into poetry. His 1986 film Hard Boiled - with its 15-minute church shootout - remains one of the most influential action sequences ever filmed. Woo didn’t just shoot guns. He choreographed them like dancers. His heroes were tragic, loyal, and often bleeding out mid-sentence. His villains? Charismatic, stylish, and always wearing sunglasses indoors.

Woo’s signature style - dual-wielded pistols, doves flying mid-gunfight, slow-motion blood sprays - wasn’t just aesthetic. It was emotional. He used bullets to express grief, honor, and sacrifice. In The Killer (1989), a hitman risks everything to help a blind singer. No one says ‘I’m sorry.’ No one needs to. The gunfire says it all.

Woo’s influence reached Hollywood fast. Quentin Tarantino called him a genius. John Travolta and Nicolas Cage tried to copy his style in Face/Off. But no one replicated it. Not because they couldn’t afford the budget. Because they couldn’t replicate the soul behind it.

The Rise of the Stunt-Driven Hero

While Woo was painting with bullets, Jackie Chan was turning buildings into playgrounds. Where Woo’s heroes moved like ghosts, Chan’s moved like acrobats. He didn’t use wires to jump from rooftops - he climbed them. He didn’t fake a punch - he got punched for real. In Police Story (1985), Chan slid down a pole made of Christmas lights, crashing through glass and plastic. The stunt took 17 takes. He broke his spine on the 15th.

Chan’s films were comedy wrapped in chaos. He made you laugh while your jaw dropped. His movies didn’t need explosions. A falling chandelier, a swinging lamp, or a collapsing shelf was enough. His genius was making danger look fun. And he made it look easy.

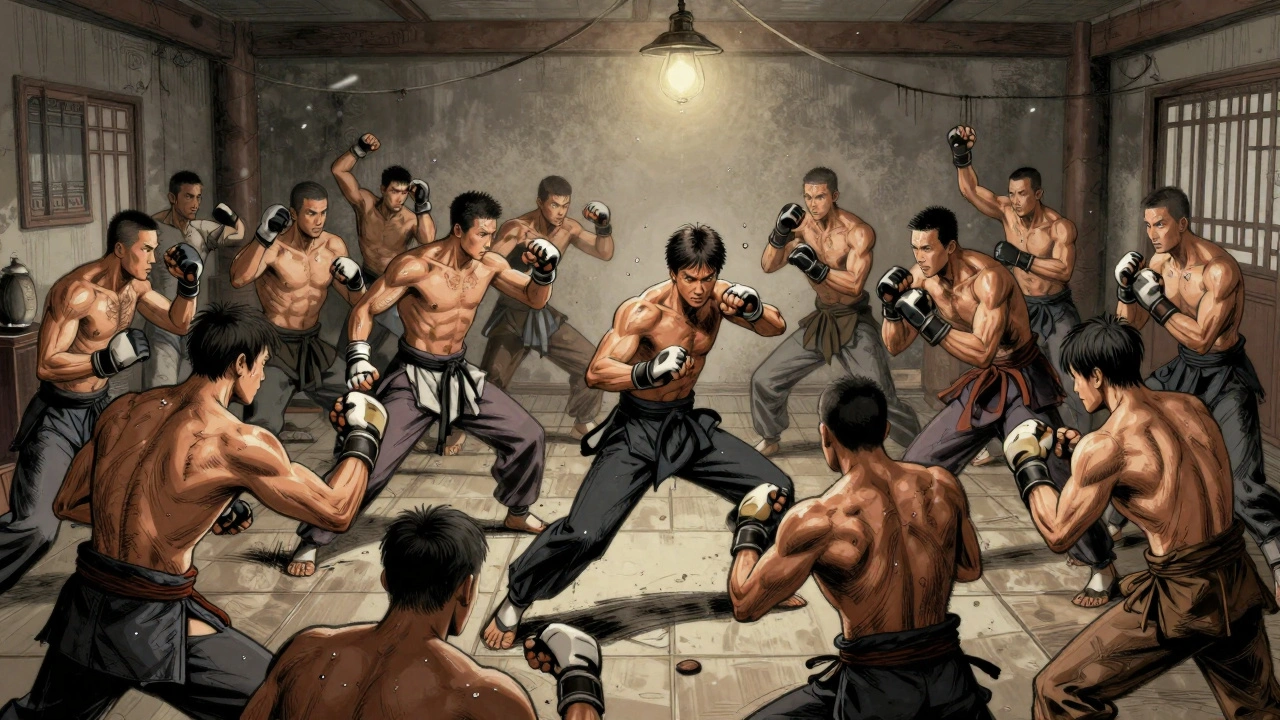

Compare that to Donnie Yen’s approach in the 2000s. Yen didn’t do slapstick. He did precision. In Ip Man (2008), every punch had weight. Every block had timing. He trained for years in Wing Chun, not for show - for truth. His fights felt like martial arts demonstrations, not movie stunts. And that’s what made them terrifying.

Gun-Fu: When Kung Fu Met Firepower

‘Gun-fu’ isn’t just a buzzword. It’s a genre. A hybrid. A fusion of traditional Chinese martial arts with modern firearms. It didn’t start with John Woo, but he perfected it. Before Woo, Hong Kong action films were mostly bare-handed. Kung fu was about discipline. Gun-fu was about desperation.

In Hard Boiled, Tony Leung’s character uses a shotgun like a staff. He spins it, blocks bullets with it, and fires from between his legs. In Once Upon a Time in Hong Kong (2020), a gangster uses a revolver to shoot a lock off a door - then kicks it open with his foot. These aren’t CGI tricks. They’re choreographed by stunt teams who’ve spent decades learning how to move with weapons like extensions of their bodies.

The key to gun-fu? Realism with flair. The guns make noise. The recoil shakes the actor. The bullets hit things you can see - walls, chairs, bottles. No invisible lasers. No magic reloads. That’s why these films still hold up. They’re grounded in physics, not pixels.

The Golden Age and the Crash

The 1980s and early 90s were Hong Kong’s golden age. Studios pumped out dozens of action films a year. Stars like Chow Yun-fat, Michelle Yeoh, and Sammo Hung were household names. The industry had a rhythm: shoot fast, edit faster, release next week. Budgets were tight. Creativity was unlimited.

Then came the handover. In 1997, Hong Kong returned to Chinese rule. Funding dried up. Studios merged. Talent moved to Hollywood or mainland China. By the early 2000s, the old system was gone. The films got bigger - but colder. More CGI. Fewer real falls. More explosions. Less heart.

By 2010, Hong Kong action cinema was a shadow of its former self. But it didn’t die. It changed.

Modern Gun-Fu: The Revival

Today, the spirit of Hong Kong action lives on - not in Hong Kong, but in the global underground. Films like The Raid (2011), John Wick (2014), and Atomic Blonde (2017) are direct descendants of Woo and Chan. They borrow the pacing, the practical stunts, the emotional weight.

Even Netflix’s The Night Comes for Us (2018) feels like a lost Hong Kong film from 1992. It’s brutal. It’s messy. It’s beautiful. And it was made by an Indonesian director, not a Hong Kong one. That’s the truth now: the style has gone global.

Donnie Yen’s Ip Man 4 (2019) was one of the last major Hong Kong-produced action films with real studio backing. It closed the door on the old era. But it also proved the legacy lives. The choreography was flawless. The performances were raw. And the final fight? One continuous shot. No cuts. No wires. Just a man, a room, and 15 fighters.

What Makes It Different From Hollywood Action?

Hollywood action is about scale. Bigger explosions. Faster cars. More CGI aliens. Hong Kong action is about intimacy. It’s about the sweat on your brow. The crack in your knuckles. The way your hand shakes before you pull the trigger.

Hollywood heroes win by luck or power. Hong Kong heroes win by will. They bleed. They cry. They get up again. Even when they’re outnumbered. Even when they’re broken.

That’s why, even now, people still watch these films. Not because they’re old. But because they feel real. In a world of digital heroes and recycled plots, Hong Kong action cinema reminds us that courage isn’t about superpowers. It’s about showing up - even when you’re scared.

Where to Start

If you’ve never seen a Hong Kong action film, here’s where to begin:

- Hard Boiled (1992) - The ultimate gun-fu masterpiece. Start here.

- Police Story (1985) - Jackie Chan at his most daring. Pure physical comedy and chaos.

- The Killer (1989) - Slow, sad, and stunning. John Woo’s emotional peak.

- Ip Man (2008) - The bridge between old and new. Real martial arts, real emotion.

- The Raid (2011) - Not Hong Kong, but the spiritual successor. No dialogue. Just fists and feet.

Watch them in order. You’ll see the evolution - from bullets to fists, from emotion to precision. And you’ll understand why, decades later, people still call these films the greatest action movies ever made.

What makes Hong Kong action cinema different from other action films?

Hong Kong action films focus on practical stunts, real choreography, and emotional weight over CGI and spectacle. They use real locations, minimal wires, and actors who perform their own stunts. The fights are designed to feel personal and grounded - even when they involve dozens of people and dozens of guns.

Is John Woo still making action movies today?

John Woo hasn’t directed a major Hong Kong action film since the 2000s. He moved to Hollywood and made films like Face/Off and Mission: Impossible 2, but none matched the raw energy of his earlier work. He occasionally directs smaller projects, but his legacy rests on the films he made between 1986 and 1995.

Why did Hong Kong action cinema decline?

The 1997 handover to China led to funding cuts, studio mergers, and talent migration. Many directors and stunt performers moved to Hollywood or mainland China. The rise of CGI also made practical stunts seem outdated to studios. Budgets shrank, creativity followed, and the industry lost its rhythm.

Are there any new Hong Kong action films worth watching?

Yes - but they’re rare. On the Job: The Missing 8 (2021) and Mad World (2016) blend action with social drama. The White Storm 2: Drug Lords (2019) has solid gun-fu sequences. Most new films are co-productions with mainland China, which means more polished visuals but less of the gritty, chaotic spirit of the old days.

Who are the modern heirs to John Woo and Jackie Chan?

Donnie Yen carries the martial arts torch with precision and discipline. Yuen Woo-ping, the legendary choreographer behind The Matrix, still trains new stunt teams in Hong Kong. In Hollywood, actors like Tom Hardy and Keanu Reeves have adopted the Hong Kong style - especially in John Wick, which is essentially a modern Hong Kong film with American funding.

Final Thought: Why This Still Matters

There’s a reason you still see Hong Kong action films referenced in video games, anime, and music videos. It’s not nostalgia. It’s admiration. These films proved you don’t need billions to make something unforgettable. You just need a camera, a few good stuntmen, and the courage to do something no one else dared.

Today, when studios chase algorithms and sequels, Hong Kong action cinema reminds us that movies can be art - even when they’re full of bullets.