Indie cinema didn’t just survive the 2020s-it exploded. While Hollywood kept chasing billion-dollar franchises, a quiet revolution happened in theaters, streaming platforms, and film festivals. Studios like A24 and Neon didn’t just release movies-they built movements. These weren’t just films with small budgets. They were bold, strange, emotionally raw, and impossible to ignore. And they made audiences forget they were watching something labeled "independent." By 2025, A24 had gone from a niche distributor to a cultural force. Neon didn’t just enter the game-they rewrote the rules. And behind them, a wave of smaller players-Focus Features, IFC Films, Magnolia, and even international outfits like Film4 and Pathé-were finding new ways to reach viewers who craved something different. This isn’t about who spent the most money. It’s about who understood something simple: audiences are tired of formula. They want films that feel real, that challenge them, that leave them thinking long after the credits roll.

How A24 Turned Weird Into Worthwhile

A24 started in 2012 as a film distribution company with no big hits and no clear plan. By 2020, they were the most talked-about studio in indie film. Their secret? They didn’t chase trends. They chased tone. Hereditary (2018) didn’t just scare people-it haunted them. The Lighthouse (2019) looked like a black-and-white nightmare from 1920, but it felt terrifyingly modern. Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022) mixed martial arts, multiverse chaos, and a mother-daughter relationship so real it made audiences cry in theaters. It won seven Oscars. No studio had ever won that many for a film that started with a $25 million budget. A24’s films don’t follow the three-act structure. They don’t always have happy endings. They often feature characters who are broken, quiet, or deeply strange. But they’re never boring. Their marketing teams leaned into that. Trailers didn’t show plot-they showed mood. Posters were minimalist art. They treated every release like a limited-edition album. And it worked. In 2024, A24’s films made up 12% of all Oscar-nominated movies, despite making less than 1% of all U.S. box office revenue. That’s not luck. That’s strategy.Neon: The Studio That Played Hardball

If A24 was the quiet genius, Neon was the loud disruptor. Founded in 2017 by former Magnolia execs, Neon didn’t wait for permission. They bought films at festivals and dropped them like bombs. Their breakout was Parasite (2019). Not just because it won Best Picture-it was the first non-English language film to do so. But because Neon didn’t treat it like a foreign film. They marketed it as a thriller. As a dark comedy. As a family drama. They didn’t say "it’s in Korean." They said, "This is the best movie of the year." They followed it up with The Worst Person in the World (2021), a Norwegian film about a woman in her late 20s trying to figure out life. It got a wide U.S. release. It made $11 million. No one expected that. Then came Anatomy of a Fall (2023), a French courtroom drama that became a global hit without a single action scene. Neon’s playbook is simple: buy the best film at Sundance or Cannes, then bet everything on its emotional core. They don’t care if it’s in Spanish, Swedish, or sign language. If it moves people, they’ll find an audience. In 2024, Neon’s films accounted for 3 of the top 10 highest-grossing indie releases in North America. One of them, The Holdovers, was a quiet 1970s-set school drama starring Paul Giamatti. It made $75 million worldwide. No explosions. No CGI. Just a man, a boy, and a snowstorm.

The Rise of the Hybrid Distributors

A24 and Neon aren’t the only ones changing the game. A new breed of distributors emerged-ones that blend traditional indie models with digital-first strategies. Focus Features, owned by Universal, used to be known for Oscar-bait dramas like Lost in Translation. In the 2020s, they started releasing films like Past Lives (2023) with no traditional marketing campaign. Instead, they partnered with TikTok creators to share personal stories about long-lost love. The film made $40 million on a $5 million budget. IFC Films and Magnolia shifted to direct-to-consumer platforms. They launched their own apps. You can now rent Swan Song (2021), a sci-fi drama about a dying man who has a clone made, directly from Magnolia’s site. No Netflix. No Hulu. Just the film and a $5.99 rental fee. Even international players got in on it. Film4, the UK’s public film fund, backed The Power of the Dog (2021) and The Banshees of Inisherin (2022). Both were co-produced with A24 and became massive hits. Film4 didn’t just fund films-they helped shape them, often giving directors total creative control. The lesson? You don’t need a giant studio. You just need a clear vision and a way to reach the people who care.What Makes an Indie Breakout in the 2020s?

So what do these films have in common? Here’s what separates the breakout indies from the ones that fade away:- They’re emotionally honest. No fake triumphs. No tidy endings. Just raw human experience-grief, confusion, longing, joy.

- They take visual risks. The Lighthouse used a 1.19:1 aspect ratio. Everything Everywhere had a bagel universe. Triangle of Sadness used a rotating camera to simulate seasickness. These aren’t gimmicks-they’re storytelling tools.

- They cast against type. Daniel Radcliffe in Swiss Army Man. Florence Pugh in Black Widow and then Don’t Worry Darling and then The Wonder. Stars aren’t just actors-they’re chameleons.

- They rely on word-of-mouth. No billion-dollar ad buys. Just Reddit threads, Instagram reels, and friends texting, "You have to see this."

- They’re made by people who’ve been told no. Most of these directors were rejected by studios 10 times before someone said yes. They didn’t go to film school. Or they dropped out. Or they made shorts on iPhones.

Where Do We Go From Here?

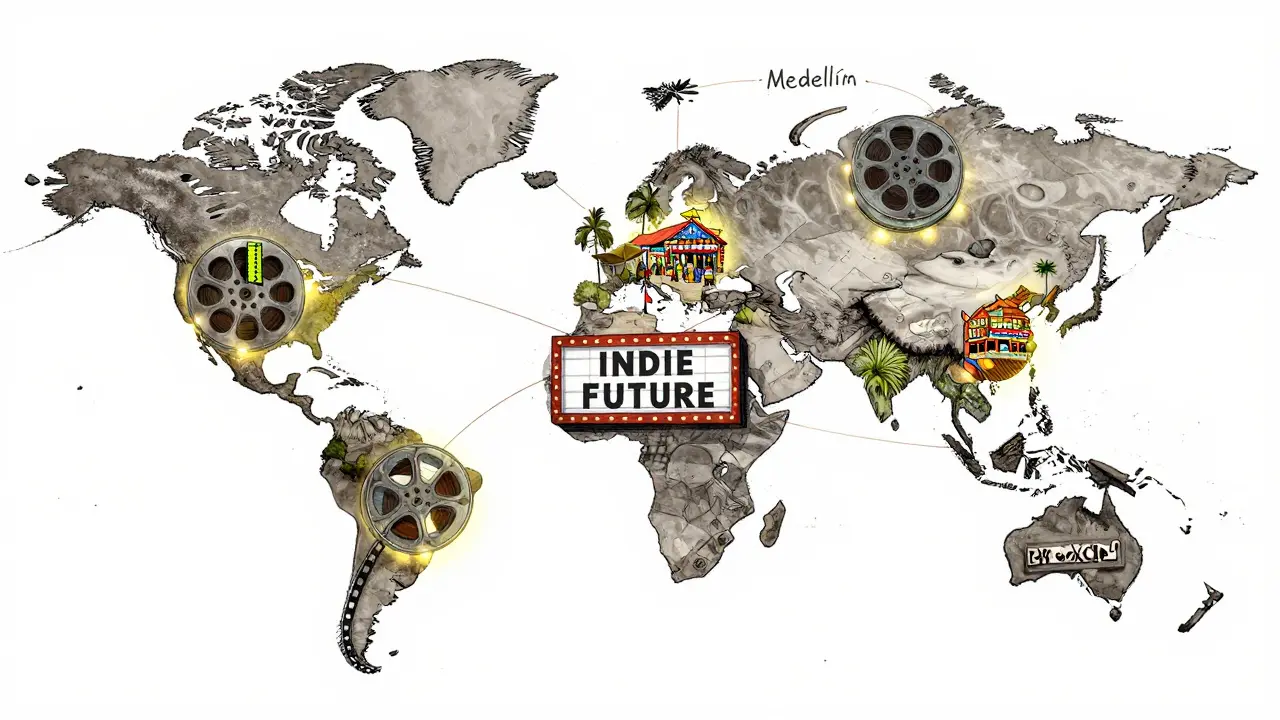

By 2025, the indie film landscape looks very different from 2010. Streaming services used to be the death of indie cinema. Now, they’re its lifeline. Netflix, Apple TV+, and Amazon Prime all have dedicated indie film teams. But they’re not replacing A24 or Neon-they’re partnering with them. Apple co-produced The Brutalist (2024), a 3.5-hour epic about a Jewish architect rebuilding his life after the Holocaust. It made $90 million. No one expected that. The next wave? More global voices. More female directors. More films from Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America. Studios are starting to realize that the best stories aren’t coming from Los Angeles. They’re coming from Lagos, Manila, and Medellín. And audiences? They’re not waiting for studios to tell them what to watch. They’re hunting for films on Letterboxd, on TikTok, on YouTube channels that review obscure foreign films. They’re curating their own cinema. The indie film revolution of the 2020s didn’t need a studio system. It needed a community.What’s Next for Indie Film?

The next few years will test whether this momentum can last. Rising production costs, union strikes, and AI-generated content are real threats. But so is the hunger of audiences for something real. Look at the 2025 Sundance lineup. Half the films were directed by women. Three were made with budgets under $100,000. One was shot entirely on a smartphone. Another used AI to generate backgrounds-but kept the actors’ performances untouched. That’s not a threat. That’s evolution. The future of indie film isn’t about bigger budgets. It’s about bolder ideas. More voices. More chances taken. And more people willing to sit in a dark theater, alone, and let a story change them.What makes a film "indie" in the 2020s?

A film is considered indie today if it’s made outside the traditional studio system-usually with a budget under $20 million, and with creative control held by the filmmakers, not executives. It doesn’t matter who distributes it; what matters is how it was made. Films like Everything Everywhere All At Once or Parasite were funded independently, even if they were later picked up by big distributors.

Are A24 and Neon the only important indie studios?

No. While A24 and Neon are the most visible, studios like IFC Films, Magnolia, Focus Features, Film4, and even international players like Pathé and Canana Films are shaping the landscape. Many breakout films come from partnerships between these smaller studios and international co-producers. The indie ecosystem is more diverse than ever.

Why do indie films win so many Oscars?

Indie films often win Oscars because they’re more willing to take creative risks-unlike big studio films, which are designed for mass appeal. Indie films tend to focus on character, tone, and emotional truth, which awards voters respond to. Plus, studios like A24 and Neon run targeted Oscar campaigns with expert publicists who know how to position films for awards season.

Can indie films still make money?

Yes-and sometimes more than blockbusters. Everything Everywhere All At Once made over $140 million worldwide on a $25 million budget. The Holdovers made $75 million with no action scenes. Indie films thrive on word-of-mouth and niche audiences. A film doesn’t need to make $500 million to be profitable. It just needs to find its people.

How do indie films get distributed today?

Most indie films now use a hybrid model: they premiere at festivals like Sundance or Cannes, then get picked up by distributors like A24 or Neon. Many also release directly through streaming platforms or their own apps. Some even self-distribute via Vimeo On Demand or YouTube. The old theatrical-only model is gone.