Latin American New Wave didn’t start with fancy cameras or big budgets. It started with real streets, real pain, and real people who had never seen themselves on screen before. In the 1960s, filmmakers across Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, and beyond began rejecting Hollywood-style storytelling. They picked up handheld cameras, cast non-professional actors, and shot in neighborhoods where police rarely came and journalists never stayed. What came out wasn’t just movies-it was a revolution.

How It All Began: The Birth of a Movement

The Latin American New Wave didn’t appear overnight. It was born from frustration. In the 1950s and early 60s, most films made in the region were either cheap imitations of American genres or sanitized musicals designed to please censors. But young filmmakers in Rio, Mexico City, and Buenos Aires were reading Godard, watching Fellini, and listening to the political unrest around them. They asked: Why should our stories be told by outsiders?

In Brazil, Glauber Rocha’s Black God, White Devil (1964) used brutal imagery and poetic voiceovers to show the suffering of peasants in the Northeast. In Argentina, Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino’s Hour of the Furnaces (1968) was a three-hour documentary-style manifesto that called cinema a weapon of liberation. These weren’t entertainment-they were calls to action.

What tied them together wasn’t style, but purpose. They filmed in real locations, used natural light, and let silence speak louder than dialogue. Their films didn’t need happy endings. They needed truth.

City of God: The Brutal Beauty of Rio’s Favelas

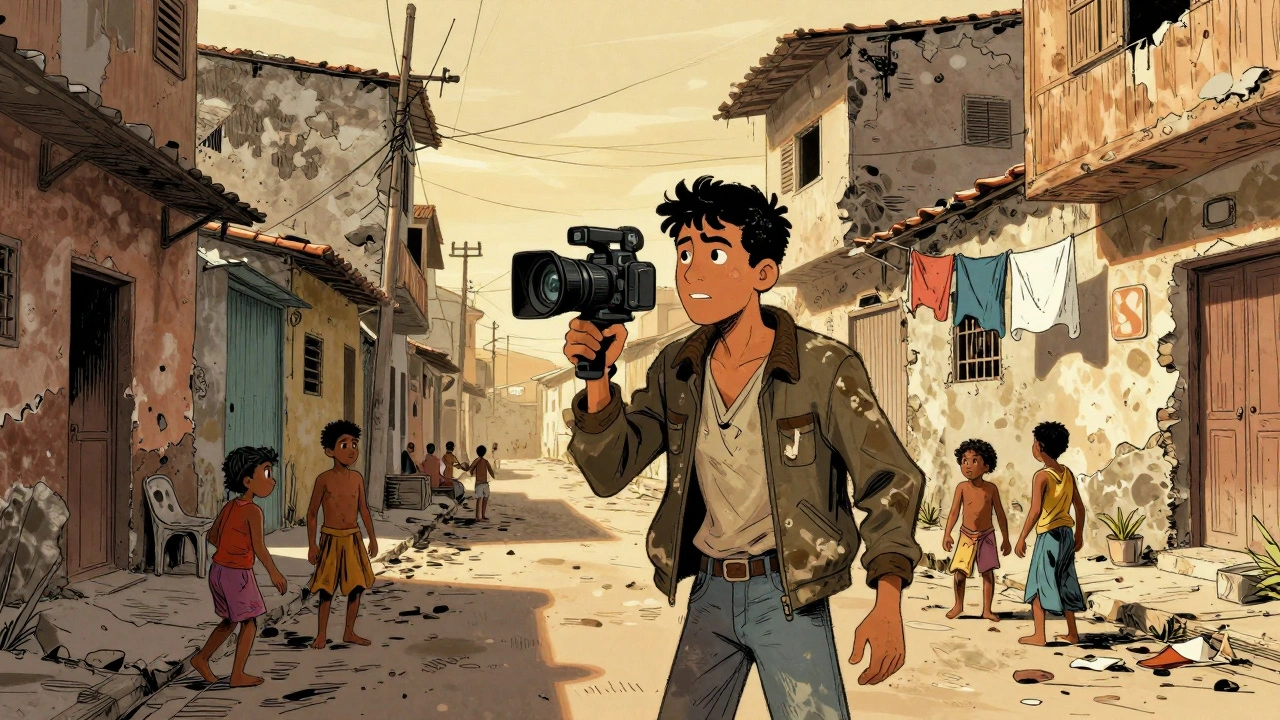

Fast forward to 2002. The New Wave had faded into memory, but its spirit was alive in Fernando Meirelles and Katia Lund’s City of God. Based on a novel by Paulo Lins, the film didn’t just depict life in Rio’s favelas-it plunged you into it. No glamor. No redemption arcs. Just survival.

The cast was mostly teenagers from the real favelas. The actors playing the gang members had never acted before. One of them, Alex Cardoso, had been a street vendor. Another, Douglas Silva, had survived a shooting. The camera didn’t stay still. It ran, jumped, spun. The editing was frantic, almost chaotic, mirroring the lives of kids who never knew a future.

The film didn’t glorify violence. It showed how it was inherited. A boy who steals a chicken grows into a drug lord. A kid who just wants to take photos ends up as a witness to everything. The camera lingers on faces-not to make them heroes, but to remind you they’re human. City of God didn’t win Oscars because it was pretty. It won because it was unbearable to look away.

Roma: The Quiet Revolution of Memory

More than 40 years after City of God, Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma (2018) did the opposite. No explosions. No chase scenes. Just a woman walking. A dog barking. Rain falling on a tiled courtyard. Yet it shook the world.

Roma is a black-and-white memory. Not a story about politics or crime, but about a domestic worker, Cleo, who holds together a middle-class family in 1970s Mexico City. Cuarón didn’t cast a star. He cast his own childhood nanny, Yalitza Aparicio, who had never acted before. The film was shot in the exact house where he grew up. The sounds-the clatter of dishes, the distant rumble of a bus-are the same ones he heard as a boy.

There’s no villain. No big twist. Just the weight of silence. Cleo doesn’t speak much. Her emotions are in her hands-washing clothes, holding a baby, standing still as the world falls apart around her. When she walks into the ocean at the end, it’s not a climax. It’s a release.

Roma proved that Latin American cinema didn’t need bloodshed to be powerful. Sometimes, all it needs is a gaze.

What Makes These Films Different?

Both City of God and Roma are rooted in the same soil: Latin America’s history of inequality, censorship, and resilience. But they show two sides of the same coin.

City of God screams. It uses color, sound, and motion to force you to feel the chaos. It’s a film made by someone who grew up watching Hollywood action movies but knew they didn’t reflect his reality. So he made his own version-faster, louder, more violent.

Roma whispers. It uses stillness, texture, and space to make you lean in. It’s a film made by someone who grew up in privilege but saw how the people who kept his home running were invisible. So he made them visible-with no fanfare, no music, no commentary.

Both films were made with limited resources. Both used real locations. Both cast non-actors. Both were rejected by studios before they found their audience. That’s not coincidence. That’s the DNA of the New Wave.

The Legacy: Who’s Carrying the Torch?

The New Wave didn’t die. It evolved. Today, filmmakers like Lucrecia Martel in Argentina, Pablo Larraín in Chile, and Amat Escalante in Mexico are pushing boundaries in ways that would make Rocha proud.

Martel’s The Headless Woman (2008) is a slow-burn mystery where the protagonist’s guilt is felt in the spaces between words. Larraín’s Spencer and Jackie show how he brings Latin American emotional realism to global icons. Escalante’s Heli (2013) is a harrowing look at drug violence that refuses to simplify good and evil.

Even streaming platforms like Netflix and Amazon have become unlikely allies. They didn’t fund the New Wave, but they’ve given its descendants a global stage. Roma was the first non-English film to win Best Picture at the Oscars. That wasn’t luck. It was the result of decades of quiet, stubborn filmmaking.

Why This Matters Today

When you watch a film from Latin America’s New Wave, you’re not just watching a story. You’re watching resistance. These films were made when governments censored art, when the poor were erased from media, when the world assumed their lives weren’t worth telling.

Today, those same voices are louder than ever. But the fight hasn’t ended. Many filmmakers still struggle to get funding. Many actors still work without contracts. Many stories still go untold because they’re too messy, too real, too uncomfortable.

City of God and Roma remind us that cinema doesn’t need permission to be great. It just needs honesty. And a camera.

Where to Start Watching

If you want to feel the pulse of Latin American New Wave cinema, start here:

- Black God, White Devil (1964) - Glauber Rocha, Brazil

- Hour of the Furnaces (1968) - Solanas & Getino, Argentina

- City of God (2002) - Fernando Meirelles, Brazil

- Roma (2018) - Alfonso Cuarón, Mexico

- The Headless Woman (2008) - Lucrecia Martel, Argentina

- Heli (2013) - Amat Escalante, Mexico

Watch them in order. Notice how the style changes, but the heart stays the same.