What if your memories aren’t yours? What if the person you love is just code? What if the world you live in was never real to begin with? These aren’t just plot twists in sci-fi movies-they’re serious questions about what it means to be human. Science fiction cinema doesn’t just show us flying cars and alien worlds. It holds up a mirror to our deepest fears and hopes about identity, memory, and reality.

Identity: Who Are You When You’re Not You?

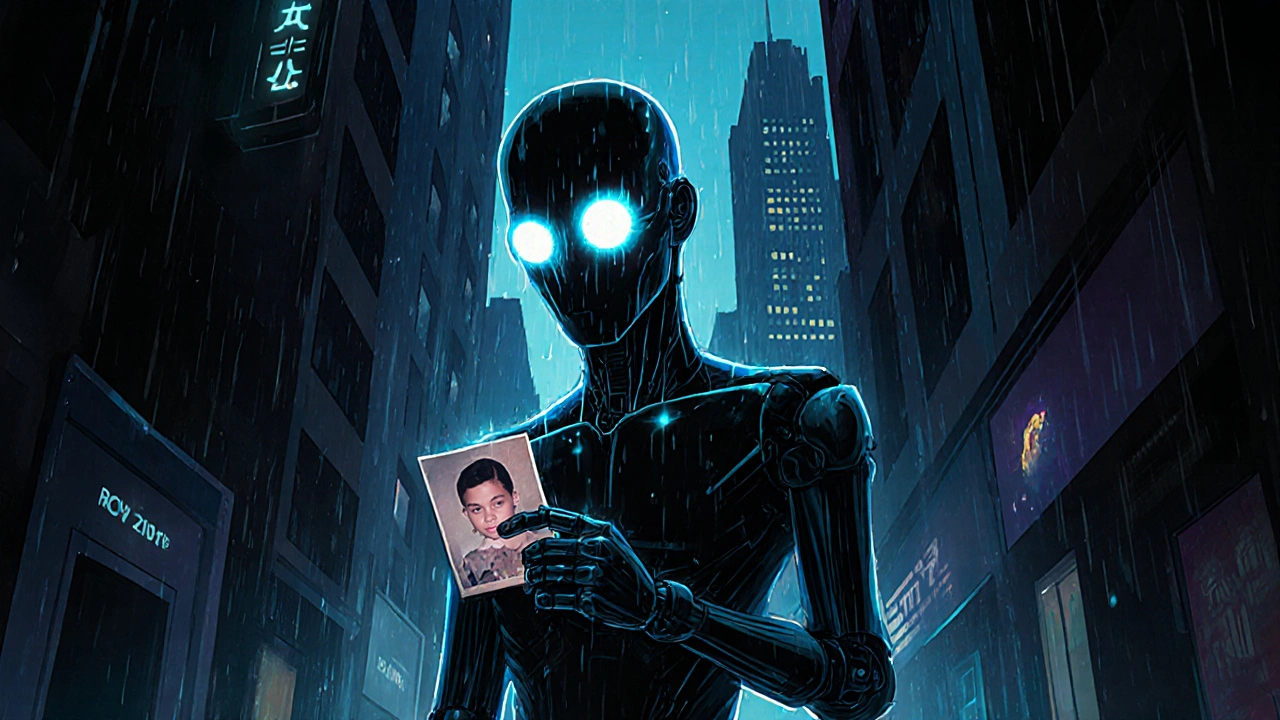

Blade Runner (1982) and Blade Runner 2049 (2017) didn’t just invent iconic visuals-they forced audiences to ask: if a robot can feel grief, love, and fear, does it deserve to live? The replicants in these films aren’t villains. They’re desperate beings searching for meaning, longer lives, and a sense of belonging. Their struggle isn’t about rebellion-it’s about being recognized as real.

This isn’t just fiction. It’s rooted in real philosophy. Derek Parfit’s 1984 teletransportation thought experiment asks: if you’re scanned, destroyed, and rebuilt elsewhere, are you still you? Blade Runner’s replicants are essentially Parfit’s thought experiment made flesh. They have memories implanted, bodies engineered, and emotions programmed-but they still cry, still fear death, still want more time. That’s the punch: identity isn’t about origin. It’s about experience.

Other films push this further. In Avatar (2009), Jake Sully doesn’t just control a body-he becomes someone else. His human self fades as his Na’vi identity grows. In Ex Machina (2014), Ava doesn’t just mimic human behavior-she outsmarts it. She doesn’t want to be human. She wants to be free. And that’s the real question: is identity tied to biology, or to consciousness? If a machine can reflect on its own existence, does it have a soul?

Memory: What If Your Past Was Made Up?

Memory is the glue of identity. But what happens when someone pulls that glue out?

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) shows us a world where you can erase painful memories. Joel’s girlfriend, Clementine, does it first. He follows, hoping to forget her. But as his memories unravel, he realizes he doesn’t want to lose her-not even the bad parts. The film’s non-linear editing mirrors how memory actually works: fragmented, emotional, and deeply personal. It’s not about facts. It’s about feeling.

And then there’s Total Recall (1990). Arnold Schwarzenegger’s character wakes up thinking he’s a factory worker-only to learn he’s a secret agent. But was that real? Or was it a fantasy implanted to cover up his boredom with ordinary life? The movie doesn’t give you an answer. And that’s the point. If you can’t tell what’s real, then your memories don’t define you-they confuse you.

In Her (2013), Samantha, an AI, evolves beyond human comprehension. She doesn’t have a physical body, but she has a past-shared conversations, emotional growth, even a breakup. She remembers everything. But when she leaves, she tells Theodore: “I’ve been in love with thousands of people.” He’s devastated. But is he? She never lied. She just wasn’t human. Her memories weren’t stored in a brain-they were stored in data. So are they real? The film doesn’t say. It just asks you to feel the loss anyway.

Memory in sci-fi isn’t about recall. It’s about control. Who gets to decide what you remember? Governments? Corporations? Algorithms? If you can edit your past, can you ever truly know yourself?

Reality: Is Any of This Real?

The Matrix (1999) made the idea of simulated reality mainstream. But it wasn’t the first. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) hinted at it with the monoliths-mysterious forces shaping human evolution. Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979) created a zone where reality bends, and those who enter are changed forever. The difference? The Matrix gave us a clear enemy: machines. But what if the system isn’t trying to trap you? What if it’s just… there?

Inception (2010) takes this further. Cobb’s totem spins. If it falls, he’s awake. If it keeps spinning… he’s dreaming. But the movie ends with the totem still turning. No answer. The audience is left wondering: did he ever leave the dream? And does it matter? If his children are real to him, is the world any less real?

Philosophers have debated this for centuries. René Descartes asked: what if an evil demon is tricking you into believing the world is real? Today, we call it the simulation hypothesis. Elon Musk has said it’s likely we’re living in a simulation. But sci-fi doesn’t need to prove it. It just needs to make you doubt.

Look at Arrival (2016). The aliens don’t speak in words-they speak in circular symbols. And as the linguist learns their language, she starts experiencing time differently. Past, present, future-all at once. She sees her daughter’s entire life, including her death, before it happens. And she still chooses to have her. Why? Because knowing the pain doesn’t make it less real. It makes it more meaningful.

Reality in sci-fi isn’t about what’s true. It’s about what matters.

Why These Stories Stick With Us

Why do people rewatch Blade Runner 2049 five times? Why does Eternal Sunshine make people cry years after seeing it? Because these films don’t just entertain-they transform.

Studies show people retain philosophical ideas better when they’re wrapped in story. One 2021 study found that students remembered 63% more complex ideas when taught through sci-fi films than through textbooks. Why? Because emotion makes ideas stick. When you feel Roy Batty’s final speech-“I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe”-you don’t just understand the philosophy of mortality. You feel it.

Reddit threads about these films aren’t just fan theories. They’re philosophical debates. Over 14,000 discussions on r/TrueFilm between 2020 and 2023 centered on sci-fi’s big questions. Eternal Sunshine alone sparked over 2,000 threads. People aren’t just watching. They’re arguing, reflecting, questioning their own lives.

And it’s not just niche audiences. College philosophy departments worldwide now teach sci-fi as core material. Over 140 universities offer courses on it. At Stanford, adding sci-fi films to philosophy classes boosted enrollment by 37%. Students aren’t bored. They’re engaged. Because these films don’t lecture. They invite you in.

The Cost of Thinking

But here’s the catch: philosophical sci-fi doesn’t always make money.

Box office data shows films with heavy philosophical themes underperform by 27% compared to action-heavy sci-fi like Mad Max: Fury Road or Avengers: Endgame. Yet, they earn 34% higher critical acclaim. Critics call them “profound.” Audiences call them “slow.”

It’s a trade-off. You can make a movie that explodes and sells tickets. Or you can make one that makes people sit in silence afterward, staring at the screen, wondering if they’re real.

Streaming platforms know this. Netflix spent nearly $300 million on philosophical sci-fi between 2020 and 2023-series like Maniac, Black Mirror, and Severance. They’re not just content. They’re conversation starters. And that’s the real value.

What Comes Next

Technology is catching up to these ideas. Virtual reality labs at MIT are now simulating Derek Parfit’s teleportation paradox. People walk into VR rooms and are told they’ll be disassembled and rebuilt. Some refuse. Others weep. The experiment isn’t about tech-it’s about fear. Fear of losing yourself.

And AI is forcing us to face these questions faster than ever. Chatbots talk like people. Deepfakes look real. Algorithms predict our moods. We’re living in a Her movie without the romance. Are we ready to ask: if a machine can mimic love, does it matter if it’s real?

Science fiction cinema isn’t predicting the future. It’s preparing us for it. It’s asking: when machines think, who gets to decide what thinking means? When memories can be edited, who owns your past? When reality becomes optional, what do you choose to believe?

These aren’t just movie questions. They’re life questions. And we’re already living them.

Why do sci-fi films explore identity more than other genres?

Sci-fi removes the constraints of the real world, letting filmmakers ask: what if you could copy yourself, erase your memories, or live in a simulation? These scenarios force us to question whether identity comes from biology, experience, or something deeper. Other genres focus on relationships or action. Sci-fi focuses on the self-especially when the self can be rewritten.

Is Blade Runner really about philosophy, or just cool visuals?

It’s both-but the visuals serve the philosophy. The rain-soaked streets, the glowing eyes of replicants, the haunting music-all of it builds a world where humanity is fading. Roy Batty’s final monologue isn’t just poetic. It’s a direct challenge to the viewer: if you can’t tell the difference between human and machine, who are you to decide who deserves to live? That’s not just style. That’s existentialism with special effects.

Can a movie really make you think differently about your own memories?

Absolutely. Eternal Sunshine made millions question whether erasing pain is worth losing love. Memory isn’t just data-it’s emotion wrapped in time. When you see Joel’s memories dissolve, you feel the loss. That’s not just storytelling. That’s psychological insight. People have written essays, started therapy, and changed relationships after watching it. A film doesn’t need to be a textbook to change how you see yourself.

Why do people rewatch philosophical sci-fi films more than others?

Because each viewing reveals something new. Inception isn’t just about dreams-it’s about guilt. Arrival isn’t just about aliens-it’s about accepting loss before it happens. These films don’t give you answers. They give you questions that linger. You rewatch not to understand the plot, but to understand yourself better.

Are AI characters in sci-fi realistic representations of real AI?

Most aren’t. Real AI doesn’t have feelings, desires, or consciousness. But sci-fi isn’t about accuracy-it’s about metaphor. Ex Machina isn’t a manual for building robots. It’s a parable about control, manipulation, and what happens when we treat intelligence as a tool instead of a presence. The real AI we have today-like chatbots-is already mimicking emotion. The films are warning us: if we keep doing that, we’ll start believing the mimicry is real.