The Father isn’t just a movie about dementia. It’s a film that makes you feel like you’re losing your mind-alongside its main character. When Florian Zeller adapted his own award-winning play for the screen in 2020, he didn’t just translate dialogue. He rebuilt the entire experience. The stage version trapped audiences in a single apartment, using shifting furniture and recurring actors to hint at disorientation. The film took that idea and turned it into a visceral, emotional rollercoaster. You don’t watch Anthony’s confusion-you live it.

How the Play Built Disorientation

The original stage version of The Father, first performed in Paris in 2012, relied on repetition and subtle changes. The same actors played different roles depending on the scene. A daughter might become a nurse. A stranger might suddenly be the son. The set didn’t change much-just a few pieces of furniture moved, lights shifted, and the audience was left wondering: Is this the same room? Is this the same person?

That’s the point. Zeller didn’t want to explain dementia. He wanted the audience to feel it. The play used minimalism to maximum effect. No flashbacks. No voiceovers. Just a man trapped in a world that kept rewiring itself. Actors had to play multiple characters with slight variations in tone, posture, and age. The audience had to piece together relationships from context alone. It was unsettling. And that was the goal.

What Changed When It Moved to Film

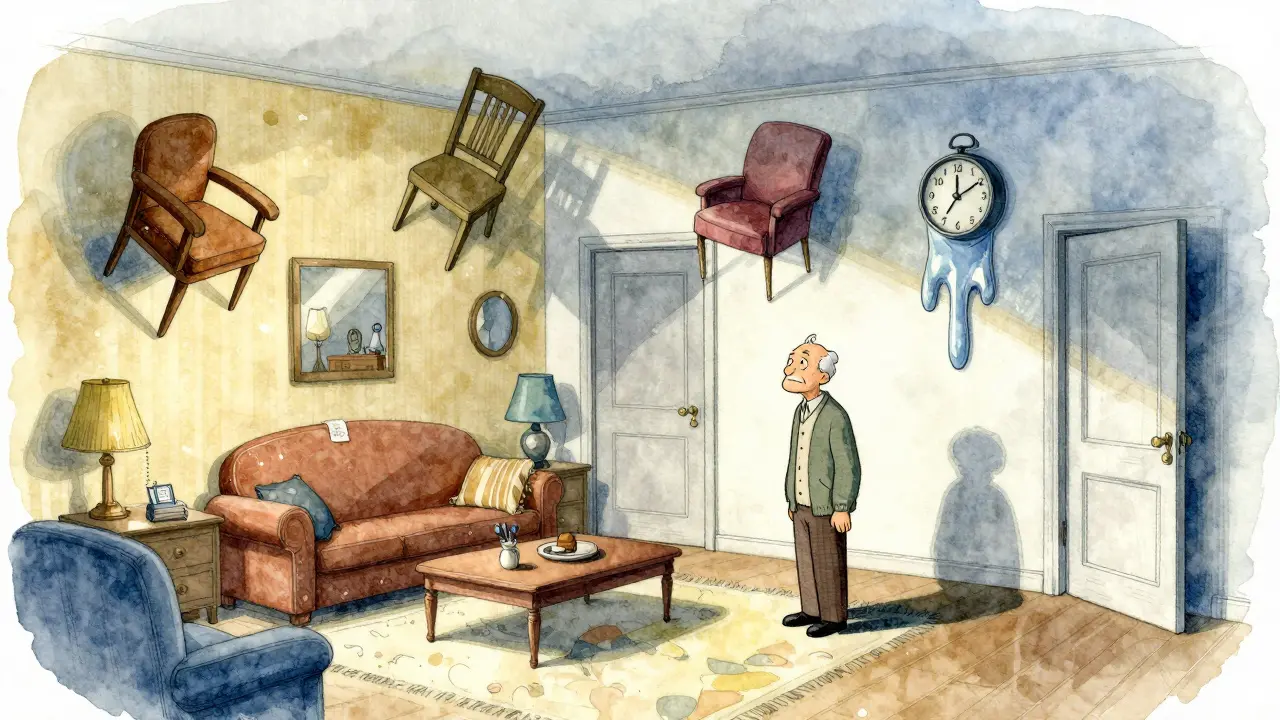

On screen, Zeller had tools the stage couldn’t offer: camera movement, sound design, editing tricks, and close-ups that lingered too long. He used them to make the confusion physical. In one scene, Anthony (played by Anthony Hopkins) walks into a room that looks exactly like his apartment-but the wallpaper is different. The clock on the wall ticks backward. A woman he thinks is his daughter calls him "Dad"-but her voice is wrong. The camera doesn’t cut away. It holds. You feel the panic building in your chest.

The film drops you into Anthony’s reality without warning. There’s no narrator. No medical explanation. No flashbacks to his past. You don’t know who’s lying. You don’t know who’s telling the truth. You don’t even know if the apartment is real. Is it his home? Is it a care facility? Is it both? The film refuses to answer. That’s what makes it so powerful.

Unlike stage productions, where the audience can look around and reorient themselves between scenes, the film traps you in the moment. Every cut feels like a glitch. Every face change feels like a betrayal. The editing doesn’t follow logic-it follows memory. And memory, when it’s breaking down, doesn’t follow logic at all.

Anthony Hopkins and the Performance of Confusion

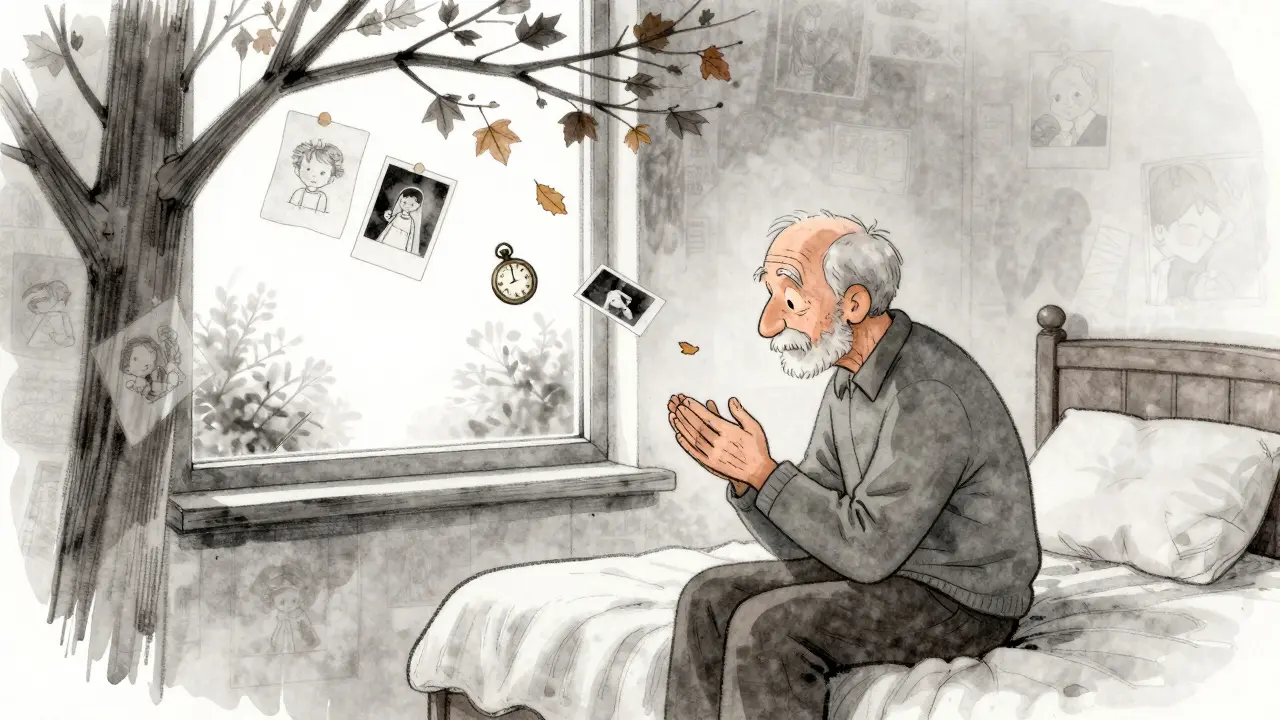

Hopkins didn’t just act a role-he embodied a mind unraveling. He didn’t rely on dramatic monologues. He used silence. A pause. A blink. A glance that lingers too long. In one quiet moment, he stares at his hands and whispers, "I feel like I’m losing everything." No music swells. No camera zooms. Just a man who knows, deep down, that he’s slipping away.

His performance earned him an Oscar, but it wasn’t about technique. It was about truth. Hopkins didn’t play dementia. He played the fear of losing yourself. The terror of not recognizing your own life. The horror of being told you’re wrong about things you know are real. That’s why the film hits so hard. It’s not about symptoms. It’s about identity.

The supporting cast-Olivia Colman, Mark Gatiss, Imogen Poots-each played multiple roles. One actor might appear as Anthony’s daughter in one scene, then as a nurse in the next. The audience, like Anthony, starts to doubt: Is this the same person? Or am I misremembering? That uncertainty is intentional. Zeller wanted viewers to question their own perception.

Why Perspective Matters More Than Plot

Most films about illness follow a clear arc: diagnosis, decline, acceptance. The Father throws that out. There’s no timeline. No doctor’s explanation. No resolution. The story doesn’t move forward-it spirals. That’s because dementia doesn’t follow a plot. It follows chaos.

By locking the audience into Anthony’s point of view, Zeller forces empathy. You don’t pity him. You become him. You start doubting your own memories. You second-guess what you saw. You wonder if the person next to you is who they say they are. That’s not storytelling. That’s immersion.

Compare this to other films about dementia, like Still Alice or Marley & Me. Those films explain the disease. They show symptoms. They offer catharsis. The Father doesn’t. It offers confusion. And that’s more honest. Real dementia doesn’t come with a script. It comes with moments that make no sense-and no way to make them make sense again.

The Technical Choices That Made It Work

Zeller worked closely with editor Yorgos Lamprinos and cinematographer Benoît Delhomme to build the film’s fractured rhythm. They used mismatched props: a clock that changes position, a door that leads to a different room, a coat that appears and disappears. These weren’t mistakes. They were clues.

Sound design played a huge role. Voices overlap. Music fades in and out without reason. A phone rings in one scene-and rings again in the next, but from a different location. The score, by Ólafur Arnalds, is sparse and haunting, like a half-remembered lullaby.

Even the lighting shifts subtly. A room that was warm and golden in one scene becomes cold and blue in the next. No one explains why. You just notice it. And you start to wonder: Did I miss something? That’s the trick. The film doesn’t trick you. It mirrors what Anthony experiences.

What the Film Gets Right About Dementia

Real people with dementia don’t forget everything at once. They forget pieces. Then they fill the gaps with guesses. They remember things that never happened. They believe people are someone else. They get angry when they’re told they’re wrong. The Father captures all of it.

One of the most chilling moments comes when Anthony, in tears, says: "I feel like I’m losing all my leaves." It’s not a line from the play. It was improvised by Hopkins. And it’s perfect. It’s poetic. It’s simple. And it’s exactly how someone with dementia might describe losing their sense of self.

The film also avoids the clichés. There’s no heroic caregiver. No tearful family reunion. No last-minute clarity before death. The daughter, Anne, is exhausted. She’s not saintly. She’s overwhelmed. She makes mistakes. She gets frustrated. She leaves the room. That’s real. Most caregivers aren’t angels. They’re people trying to hold it together.

Why This Adaptation Stands Out

Most stage-to-screen adaptations try to "open up" the story. They add new locations. New characters. New subplots. Zeller did the opposite. He made the world smaller. He tightened the focus. He used the tools of cinema to deepen the psychological trap.

He didn’t need to show hospitals or therapy sessions. He didn’t need to explain Alzheimer’s. He just needed to show what it feels like to be inside a mind that no longer trusts itself.

That’s why The Father works as both a play and a film. The stage version made you think. The film makes you feel. And that’s the difference between observation and experience.

What You’ll Remember After It Ends

You won’t remember the plot. You won’t remember who played which role. You won’t remember the exact sequence of scenes.

You’ll remember the fear.

You’ll remember the moment you realized you couldn’t trust what you were seeing.

You’ll remember the silence after the credits rolled.

And you’ll wonder-just for a second-if you’re still in control of your own mind.

Is The Father based on a true story?

No, The Father is not based on a true story, but it’s deeply rooted in real experiences. Playwright Florian Zeller wrote it after watching his own mother struggle with dementia. He didn’t set out to make a documentary-he wanted to capture the emotional truth of losing your grip on reality. The characters aren’t real people, but the feelings they express are.

Why does the setting keep changing in The Father?

The changing setting reflects Anthony’s deteriorating memory. His apartment isn’t actually moving-it’s his mind that’s rewriting the space around him. One room becomes another. Furniture shifts. Doors lead to unfamiliar places. These aren’t errors in production-they’re visual metaphors for how dementia distorts perception. The film uses environment to show internal chaos.

How accurate is The Father’s portrayal of dementia?

Medical professionals and caregivers have praised The Father for its accuracy. It captures key symptoms: confabulation (making up stories to fill memory gaps), paranoia, mood swings, and the frustration of being misunderstood. It doesn’t show every stage of dementia, but it gets the emotional core right: the terror of losing yourself while others still see you as the same person.

Can you watch The Father if you’ve never seen the play?

Absolutely. The film stands completely on its own. While the play uses repetition and minimalism to build tension, the film expands that into a sensory experience. You don’t need to know the stage version to understand or feel the film. In fact, many viewers find the movie more powerful because it doesn’t rely on prior knowledge.

Why did Anthony Hopkins win an Oscar for this role?

Hopkins didn’t just act-he disappeared into a mind unraveling. He avoided melodrama. His performance was quiet, subtle, and terrifyingly real. He showed fear without crying, confusion without shouting, and loss without explanation. Critics called it the performance of his career because it didn’t ask for sympathy-it demanded understanding. He made the audience feel what it’s like to lose your own story.