What if the most powerful moments in a documentary aren’t planned, scripted, or staged-but stumbled upon? That’s the heart of cinéma vérité. It’s not about capturing perfect shots. It’s about being there when someone breaks down, laughs uncontrollably, or stares into silence because they can’t find the words. The goal? To film life as it happens, without stepping in, without directing, without pretending the camera isn’t there. But here’s the catch: you can’t not be there. The camera changes everything. And that’s where the real challenge begins.

Where It All Started: Truth, Not Drama

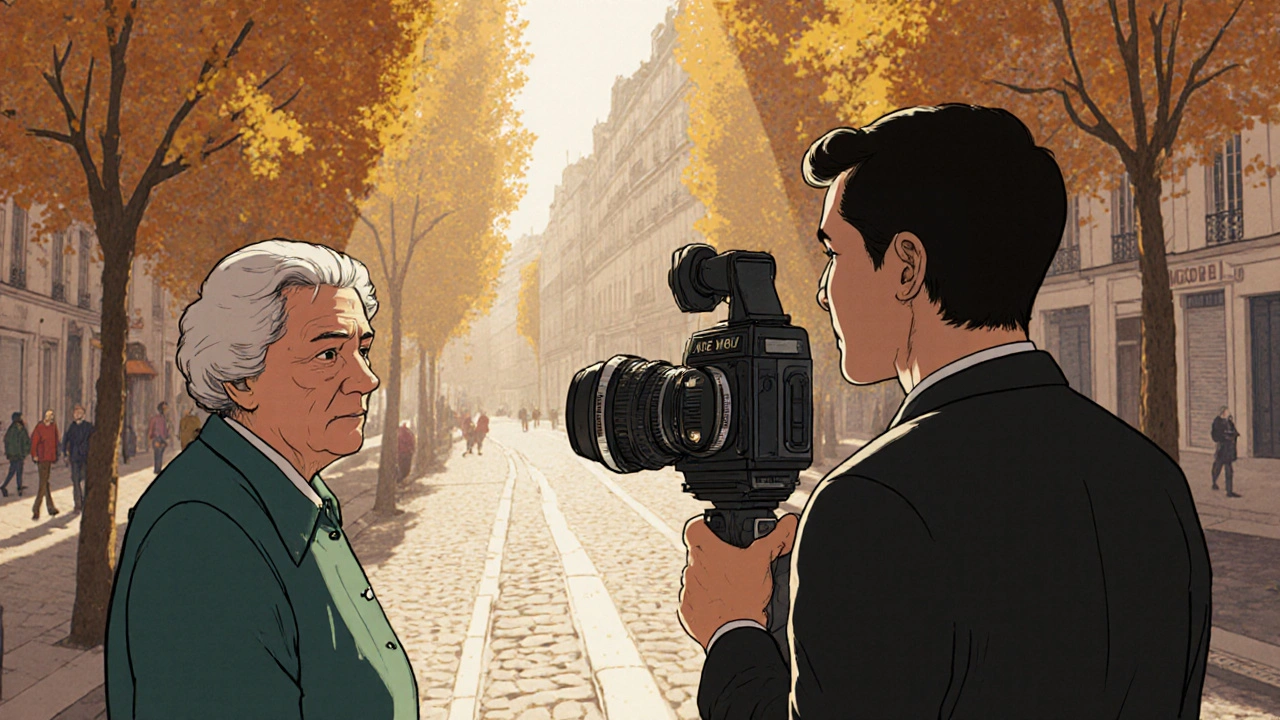

In 1961, French filmmaker Jean Rouch and sociologist Edgar Morin walked the streets of Paris with a handheld camera and a tape recorder. They didn’t ask people to act. They asked: “Are you happy?” That simple question, recorded on film, became Chronicle of a Summer-the film that launched cinéma vérité. No studio lights. No scripts. No voice-over narration telling you what to feel. Just real people, in real time, reacting to questions they hadn’t prepared for. This wasn’t newsreel journalism. It wasn’t propaganda. It was a radical experiment: What happens when you stop controlling the story and start listening? The answer was messy, emotional, and startlingly honest. People cried. People lied. People changed their minds on camera. And for the first time, audiences saw truth that couldn’t be written. The tools were primitive by today’s standards-a 10.5-pound Arriflex 16BL camera and a 7.7-pound Nagra III tape recorder. But their portability changed everything. Filmmakers could follow people into kitchens, hospital rooms, and subway cars. They could shoot in natural light, with no tripod, no boom mic, no assistant holding a reflector. The camera became an extension of the eye, not a barrier between the filmmaker and the world.Access: How Do You Get People to Let You In?

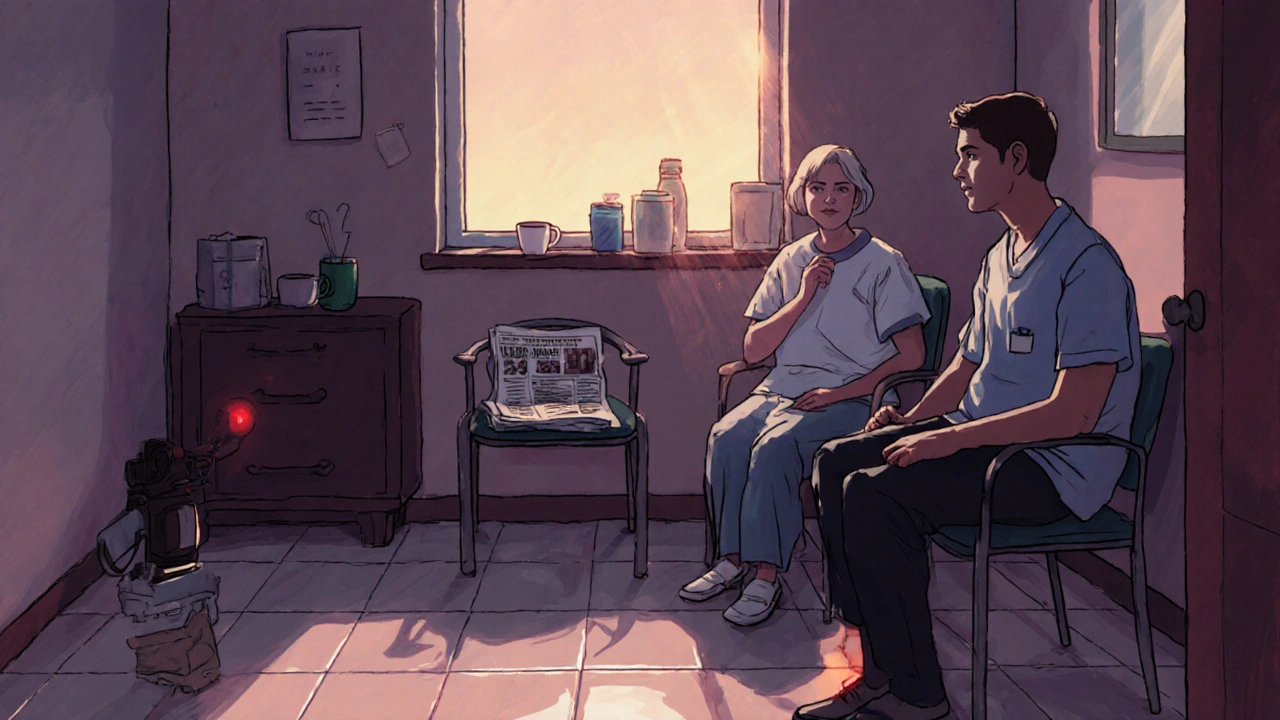

You can’t just show up with a camera and expect people to open up. In Rouch’s work, filmmakers spent months living among their subjects before pressing record. One filmmaker spent 12 weeks sitting in a hospice waiting room, drinking coffee with nurses and patients, before anyone even noticed the camera. That’s not luck. That’s strategy. The key is presence, not pressure. People don’t trust strangers with lenses. They trust people who are quiet, consistent, and patient. A 2010 study by anthropologist David MacDougall found that 83% of successful vérité projects had at least three months of pre-filming immersion. That’s not a suggestion-it’s a requirement. If you want access to someone’s grief, their joy, their secrets, you have to earn it by being there before the camera rolls. And it’s not just about time. It’s about reciprocity. In Nanfu Wang’s Hooligan Sparrow, she filmed Chinese activists under police surveillance. To get footage out of the country, she hid memory cards in toothpaste tubes. Why? Because the subjects trusted her enough to risk everything. That trust didn’t come from a contract. It came from shared risk.Intimacy: When the Camera Becomes a Mirror

The most haunting moments in vérité documentaries aren’t the big events-they’re the quiet ones. A mother staring at her child’s empty bed. A man laughing while he talks about losing his job. A teenager who says, “I don’t know who I am anymore,” and then looks away. This intimacy doesn’t happen because the filmmaker is skilled. It happens because the subject forgets the camera is there. Or, more accurately, they stop seeing it as a threat. Rouch called this the “mirror effect.” When subjects watch the dailies-the raw footage shot the day before-they often react differently. They see themselves. They question their own words. In Chronicle of a Summer, some participants cried watching themselves. Others got angry. One woman refused to be filmed again until she saw the final cut. That’s the power of vérité: it doesn’t just capture truth-it forces people to face it. Modern filmmakers still use this. In Garrett Bradley’s Time, filmed over seven years, the subject watches early footage and says, “I didn’t realize how much I’d changed.” That moment wasn’t staged. It was earned.

Filming Without Interference: The Impossible Goal

Here’s the paradox: the moment you start filming, you interfere. Bill Nichols, a leading documentary theorist, called this the “paradox of participation.” The camera invites truth-but it also distorts it. When you ask someone, “Are you happy?” you change the answer. When you follow someone into their home, you change their behavior. Even the sound of the camera’s motor can make someone pause, stiffen, or lie. Direct cinema, the American cousin of vérité, tried to solve this by becoming invisible. Robert Drew and D.A. Pennebaker used silent cameras and avoided interaction. But even they admitted: you can’t disappear. People know you’re there. They just pretend not to care. Cinéma vérité takes a different approach. Instead of pretending to be invisible, it embraces the camera’s presence. The filmmaker doesn’t hide. They ask questions. They react. They cry with the subject. In Rouch’s films, you often hear the filmmaker’s voice. That’s not a mistake. It’s the point. The question isn’t whether to interfere. It’s how to interfere ethically. The best vérité filmmakers don’t manipulate. They provoke gently. They create conditions where truth emerges-not because they forced it, but because they made space for it.What Goes Wrong: When Truth Becomes Harm

Not every vérité film ends with insight. Some end with pain. In 1973, PBS aired An American Family, a 12-episode series following a California family. The cameras rolled for 300 hours. The family’s son, Lance Loud, became the first openly gay man on American TV. But after the show aired, his parents divorced. His siblings cut ties. Lance later said, “They didn’t film our reality-they created a reality where I was the gay son.” That’s the danger. When access becomes exploitation, when intimacy becomes performance, when truth becomes spectacle. The 2019 BBC documentary The Paedophile Hunter was pulled after subjects sued for entrapment. The filmmakers didn’t just observe-they set up sting operations. The line between documenting and participating had vanished. Even the most well-intentioned projects can backfire. A 2023 University of Southern California study found that 61% of vérité subjects reported post-filming trauma. One woman, filmed during her cancer treatment, said, “I felt like I was being watched while I died.” That’s why ethical guidelines now exist. The International Documentary Association’s 2022 standards require filmmakers to hold one-hour review sessions with subjects before final edits. Subjects can ask for scenes to be cut. They can request changes. They can walk away. This wasn’t always the case. But it should be.

Modern Tools, Same Rules

Today, you don’t need an Arriflex or a Nagra. A Sony FX3, a Canon C70, or even a smartphone with a good mic can capture the same rawness. Digital sensors now handle low light like 1960s film stock never could. Dual-base ISO 800/3200 means you can shoot in dim hospital rooms or at night without lighting rigs. But the rules haven’t changed. You still need patience. You still need presence. You still need to earn trust before you earn footage. The shooting ratio for vérité projects is 42:1-42 hours of footage for every hour used. That’s because you’re waiting. Waiting for the moment when someone forgets the camera. When the mask drops. When the truth slips out. Frederick Wiseman, who’s made 45 vérité films since 1967, still makes 94% of his editing decisions while shooting. He doesn’t wait until the end. He knows, in the moment, what’s real. He knows when to keep rolling and when to step back.Why It Still Matters

In a world of curated Instagram lives, scripted TikTok dramas, and AI-generated news, vérité is the last refuge of unfiltered humanity. Netflix spends $1.2 billion a year on vérité-style documentaries. Why? Because audiences crave authenticity. They’re tired of polished lies. They want to see the sweat, the silence, the cracks. The technique isn’t perfect. It’s messy. It’s risky. It can hurt people. But when it works-when a subject says something they didn’t know they felt, when a family finally speaks after years of silence, when a society sees itself reflected without filters-that’s when cinema becomes more than entertainment. It becomes witness. Jean Rouch, days before he died in 2004, said: “The camera is not a mirror but a heart-it must beat with the subject to find truth.” That’s the only rule that matters.What’s the difference between cinéma vérité and direct cinema?

Cinéma vérité actively engages subjects-filmmakers ask questions, create situations, and sometimes even argue on camera. Direct cinema tries to be invisible, observing without interacting. Vérité seeks emotional truth through participation; direct cinema seeks factual truth through observation. Both aim for realism, but vérité admits the camera changes things, while direct cinema pretends it doesn’t.

Do you need special equipment for vérité filmmaking?

You don’t need vintage gear, but you need portability and quiet operation. Modern digital cameras like the Sony FX3 or Canon C70 work well because they’re lightweight, handle low light, and record clean sync sound. A good lavalier mic and a handheld rig are essential. The key isn’t the gear-it’s the ability to move quickly, shoot without lighting, and capture sound without a boom operator getting in the way.

How long does it take to make a vérité documentary?

There’s no set timeline, but most successful projects take 6 months to 3 years. The pre-filming immersion phase-building trust-often takes 3 to 6 months. Shooting can last months or years, depending on the subject. Editing is slow too: with 42:1 shooting ratios, you’re sifting through hundreds of hours to find 60 minutes of truth. Garrett Bradley’s Time took seven years.

Is vérité filmmaking ethical?

It can be-if done responsibly. The risk is exploitation: filming trauma without consent, creating false narratives, or violating privacy. Ethical vérité requires informed consent, subject review of footage, and the right to withdraw. The International Documentary Association now requires filmmakers to hold review sessions with subjects before final cuts. Without these safeguards, vérité becomes voyeurism.

Can vérité work for corporate or commercial projects?

Rarely, and with caution. Most corporations want polished, uplifting stories. Vérité reveals flaws, tensions, and uncomfortable truths. Only 8 Fortune 500 companies used pure vérité in 2022. It’s possible-like filming frontline workers without scripting-but it requires extreme trust and a willingness to show the messy side of business. Most brands avoid it because they can’t control the outcome.