The Academy Awards didn’t just update a name - they changed how the world sees non-English cinema. In 2019, the Best Foreign Language Film category was officially renamed to Best International Feature Film. The change took effect for the 2020 Oscars, and it wasn’t just cosmetic. It was a response to decades of criticism, cultural blind spots, and a film industry that had moved far beyond the idea of ‘foreign’ as a label.

What Was Wrong with ‘Foreign’?

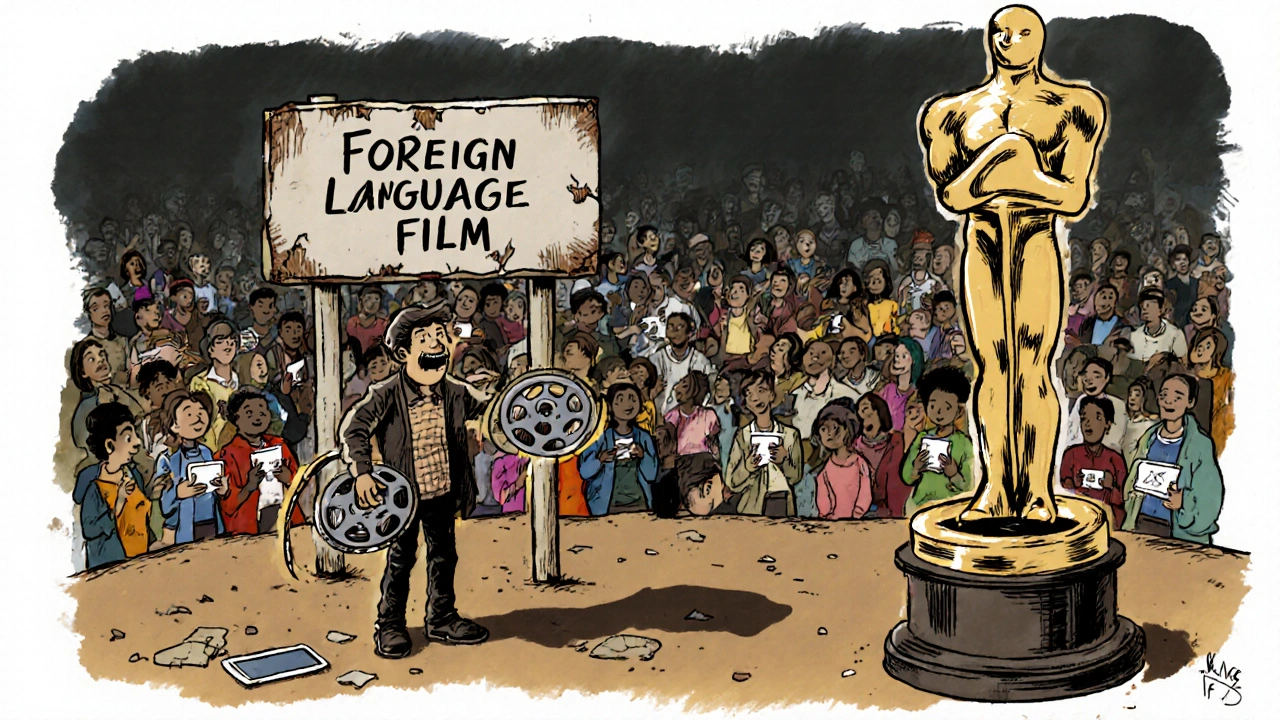

The word ‘foreign’ sounds neutral, but in practice, it carried weight. It implied distance. Otherness. Something outside the norm. For a category meant to celebrate global storytelling, calling films ‘foreign’ positioned American cinema as the default - the standard. Everything else was an outsider. That framing didn’t just feel outdated; it was actively harmful. It made non-English films seem like niche curiosities rather than vital parts of world cinema. Filmmakers and critics called it out. Bong Joon-ho, director of Parasite, famously said the Oscars felt ‘very local’ - a jab at how the industry treated non-English films as separate, not equal. Film scholar Dr. Maria San Filippo pointed out that ‘foreign’ had long been used as a marketing tool: distributors would slap the label on posters to make films seem exotic, then limit their release to art-house theaters. The term didn’t honor the work - it boxed it in. The Academy admitted it. Then-president John Bailey said the word ‘foreign’ had become ‘increasingly irrelevant’ in a world where films cross borders daily. Netflix, Amazon, and Apple TV+ were streaming Korean dramas, Spanish thrillers, and Indian epics to millions. Audiences weren’t thinking ‘foreign’ - they were thinking ‘good story.’ The Oscars needed to catch up.Eligibility Didn’t Change - But the Perception Did

Here’s the key: the rules stayed the same. A film still needs to be produced outside the U.S. and have more than 50% non-English dialogue. It still needs a seven-day theatrical run in its home country. Subtitles are still required. The award still goes to the country that submits it, not the director or studio. But the name change shifted how people saw those rules. Take Flow (2024), the Latvian animated film with no dialogue at all. It was nominated for Best International Feature Film. Under the old name, that would’ve seemed absurd - how can a film without language be ‘foreign language’? But with ‘International Feature,’ the focus shifted to origin, culture, and artistic intent - not just spoken words. Meanwhile, Nigeria’s Lionheart (2019) was disqualified because it had too much English. That rule still stands. The category isn’t about nationality - it’s about language. But the old name made people think it was about countries. The new name helps clarify: this isn’t a contest of nations. It’s a celebration of films made outside the U.S. with non-English voices.

Who Benefits From the New Name?

The biggest winners? Audiences. Streaming platforms. And filmmakers outside the Western canon. Netflix reported a 22% jump in viewership for films labeled ‘International Feature’ after the rename. On Letterboxd, average ratings for these films rose from 3.4 to 3.9 out of 5 - a clear sign that casual viewers dropped their biases. When a film isn’t labeled ‘foreign,’ people don’t assume it’s ‘hard to watch’ or ‘too slow.’ They just watch it. Film festivals saw confusion at first. Sundance accidentally printed ‘International Foreign Feature’ in its 2020 program. But within months, distributors, theaters, and critics adopted the new term. The change forced everyone to rethink how they talked about global cinema. No more ‘those foreign films.’ Just films - from everywhere. The industry also noticed a shift in how films were marketed. Instead of selling a movie as ‘an emotional Korean drama about a poor family,’ promoters could now say: ‘a powerful story about class and survival - from South Korea.’ The focus moved from difference to universality.The Numbers Still Tell a Different Story

Let’s be clear: renaming the category didn’t fix systemic bias. Between 2010 and 2023, only 6.2% of all Oscar nominations went to non-English films, according to the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative. Of the 74 winners since 1956, 58 are from Europe. Italy has 14 wins. France has 12. Nigeria? Zero. India? One nomination in 2024. Portugal has submitted over 40 times - never even made the shortlist. And while Parasite made history as the first non-English film to win Best Picture in 2020, it’s still the only one. Only 12 of the 93 International Feature nominees from 2020 to 2023 received any other Oscar nods. The category remains a ghetto - just with a nicer name. Critics like David Ehrlich of IndieWire warned that the rename was ‘woke-washing’ if the Academy didn’t change its voting body or submission process. And he’s right. The voters are still mostly white, mostly American, mostly older. The real change needs to happen in the room where the ballots are counted - not just on the poster.

What’s Next for the Category?

The Academy hasn’t stopped evolving. In 2022, it required full English subtitles for every International Feature submission - not just key scenes. That’s a big deal. It means more films are now accessible to voters who don’t speak the language. It also raises the bar for production quality. In 2024, the first fully silent film - Flow - was nominated. That forced the Academy to clarify: ‘predominantly non-English dialogue’ doesn’t mean ‘must have dialogue.’ It’s a sign the rules are adapting to modern filmmaking. Some analysts, like Scott Feinberg of The Hollywood Reporter, now wonder if the category will disappear entirely. With All Quiet on the Western Front (2022) earning nine nominations - including Best Picture - the line between ‘international’ and ‘mainstream’ is blurring. Maybe in five years, a German, Japanese, or Nigerian film will be nominated for Best Picture without needing a separate category. But for now, the Academy insists the category is still essential. It’s the only formal space where non-English films get spotlighted. Without it, many would never be seen by American audiences. The name change didn’t erase inequality - but it started a conversation.What This Means for You

If you’re a film lover, the name change is a cue to rethink what you watch. Don’t skip a film because it’s ‘foreign.’ Look for it because it’s powerful. Because it’s different. Because it’s good. If you’re a filmmaker outside the U.S., this shift matters. It tells you your story has a place - not as an outsider, but as part of the global conversation. And if you’re just curious? Start with the last five winners: Parasite (South Korea), Minari (U.S.-Korea co-production, submitted by South Korea), Drive My Car (Japan), RRR (India, 2023 nominee), and The Quiet Girl (Ireland, 2022 winner). Watch them. See how they’re not ‘foreign.’ They’re just films - made by people who happen to speak other languages. The Oscars didn’t fix everything. But they took a step. And sometimes, that’s where change begins.Why did the Oscars change ‘Best Foreign Language Film’ to ‘Best International Feature Film’?

The Academy changed the name in 2019 because the term ‘foreign’ was seen as outdated and exclusionary. It implied that non-English films were outsiders, while American cinema was the default. The new name, ‘Best International Feature Film,’ better reflects the global nature of cinema and removes the cultural bias embedded in the word ‘foreign.’

Do the eligibility rules for the award still require a film to be in a non-English language?

Yes. To be eligible, a film must be produced outside the United States and have more than 50% non-English dialogue. It must also have a seven-day theatrical run in its home country and include full English subtitles. The name change didn’t alter these requirements - only how the category is described.

Can a film with no dialogue be nominated for Best International Feature Film?

Yes. The 2024 nominee Flow from Latvia had no spoken dialogue at all. The Academy clarified that ‘predominantly non-English dialogue’ doesn’t mean dialogue must be present - only that if dialogue exists, it must be mostly non-English. Silent or minimal-dialogue films are eligible if they meet the other criteria.

Why was Nigeria’s Lionheart disqualified in 2019?

Lionheart was disqualified because over 50% of its dialogue was in English. Even though it was Nigeria’s official submission and directed by a Nigerian filmmaker, the Academy’s rule requires a film to be predominantly non-English to qualify. The category is based on language, not nationality.

Has the name change led to more non-English films winning major Oscars?

Not significantly. Parasite remains the only non-English film to win Best Picture. Since the rename, only 12 of the 93 International Feature nominees received additional Oscar nominations in major categories. The name change improved perception and marketing, but systemic bias in voting and representation remains.

How has streaming impacted the visibility of international films?

Streaming has dramatically increased access. In 2023, 65% of Netflix’s 221.6 million subscribers watched non-English content, with Korean, Spanish, and Indian films leading. Global box office revenue for non-English films reached $18.7 billion in 2023 - up from $15.2 billion in 2019. Platforms like Netflix and Amazon have made these films mainstream, pushing the Oscars to reconsider how they categorize them.