Getting the music right in a film isn’t just about writing beautiful melodies. It’s about listening-really listening-to what the director isn’t saying. The best film scores don’t announce themselves; they breathe with the scene. And that only happens when the composer and director are on the same wavelength.

What a Director Really Wants from the Music

Most directors don’t walk in saying, "I want a string quartet with a theremin." That’s not how it works. They say things like, "I need the audience to feel like something’s about to break," or "This moment should feel like memory, not reality." Those are the clues. The music has to carry the emotional weight the visuals alone can’t.

Take a scene where a character sits alone in a dark kitchen after a fight. The director might say, "Don’t make it sad. Make it empty." That’s not a musical instruction-it’s a psychological one. The composer’s job is to translate that into silence, a single sustained note, or a distant piano phrase that fades before it fully resolves. The wrong music turns that moment into melodrama. The right music makes the viewer hold their breath.

How Creative Briefs Actually Work (Not What You Think)

A creative brief isn’t a document full of technical notes. It’s a conversation captured in writing. The best ones include:

- Emotional tone: "This should feel like regret, not grief."

- Reference tracks: Not "like Hans Zimmer," but "like the ambient hum in the opening of Blade Runner 2049-but colder."

- What to avoid: "No percussion. No brass. No crescendos."

- Timing cues: "The music should enter 1.2 seconds after the door closes."

- Character perspective: "This isn’t about the mother. It’s about what the daughter hears in her head."

One composer I know got a brief that just said: "It should sound like the silence after a scream." He spent three weeks recording water dripping in an abandoned church, then slowed it down until each drop stretched into a low, trembling tone. The director cried when he heard it. That’s the goal.

Why Most Collaborations Fail (And How to Fix It)

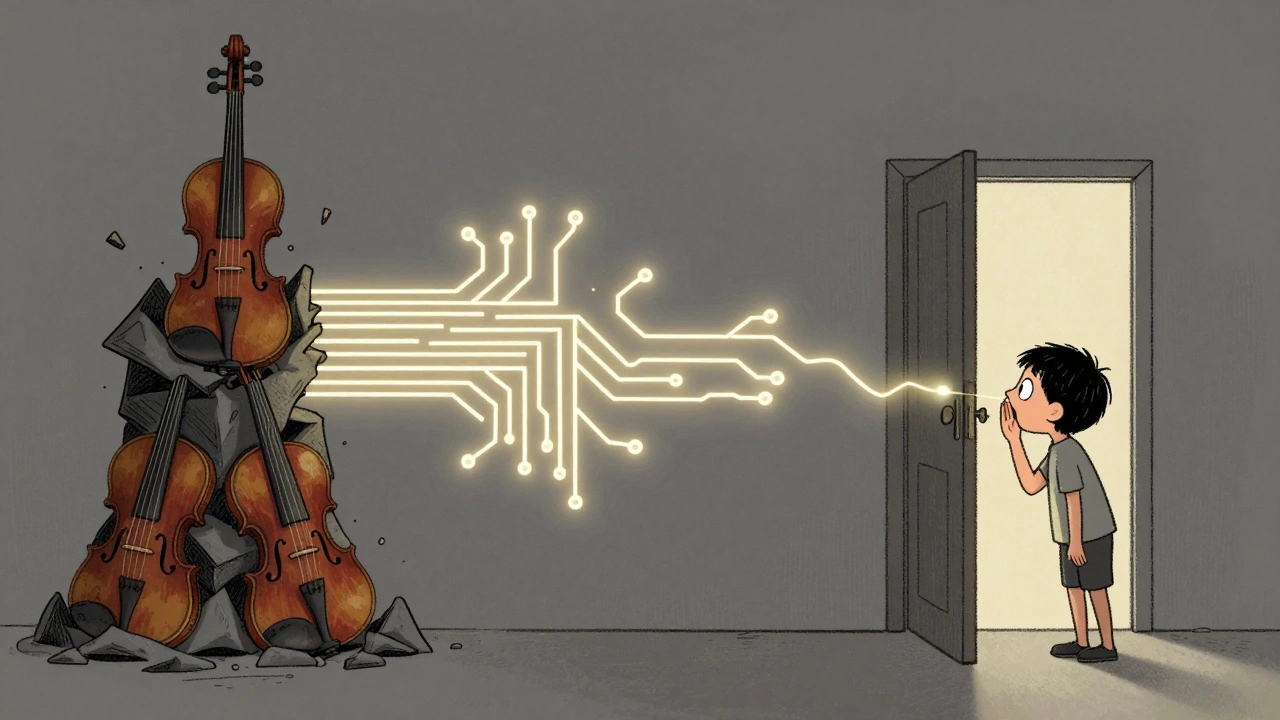

Too often, composers send a demo and get back: "It’s nice, but not what I imagined." That’s not a critique-it’s a communication breakdown. The director didn’t know how to describe what they wanted. The composer didn’t know how to ask.

Here’s what works:

- Ask for emotional keywords first. Not "orchestral," not "electronic." Ask: "If this scene had a smell, what would it be?" or "What color is the sound in this moment?"

- Watch the scene together-silently. Then talk. No music. Just reaction.

- Don’t offer options too early. One strong idea, fully developed, beats five half-baked ones.

- Be ready to scrap everything. The director might hate your 45-minute score after three weeks. That’s not failure. That’s alignment.

There’s a myth that directors are controlling. They’re not. They’re terrified of getting it wrong. Your job isn’t to please them. It’s to help them find what they’re afraid to say.

Tools That Actually Help (Not Just Fancy Software)

You don’t need a 120-piece orchestra to get the point across. In fact, most directors respond better to simple, raw ideas.

- A handheld recorder. Record yourself humming or tapping on a desk. Play it back. Sometimes the first instinct is the right one.

- Temp tracks with clear notes. If you use a temp score, write down exactly why you chose it: "Used this because the rhythm mimics a heartbeat slowing down."

- Shared mood boards. Not just images-include sounds. Link to field recordings, ambient tracks, even songs from other films that evoke the right feeling.

- A shared document with a running list of "what works" and "what doesn’t." Update it after every meeting.

One director I worked with kept a Google Doc titled "Sounds That Stick." It had entries like: "The creak of the floorboard in scene 7-keep that texture," or "The breath before the line-don’t bury it under music." That document became our bible.

When the Director Says "I Don’t Know What I Want"

This happens more than you think. And it’s not laziness. It’s uncertainty. The film is still forming in their head. Your job isn’t to fix it-it’s to give them something to react to.

Try this: Play three short, radically different ideas in a row. No explanation. Just hit play. Watch their face. Then ask: "Which one made you feel the most uncomfortable?" That’s usually the right direction. People know when something feels true, even if they can’t explain why.

One time, I played a director a full orchestral version, a lo-fi synth loop, and a recording of a child whispering a lullaby. He picked the whisper. We built the entire score around it. The film won an award for its sound design. No one expected it.

How to Handle Notes Without Losing Your Vision

Notes are inevitable. But not all notes are equal. Learn to separate:

- Directional notes: "Make it darker," "Faster pace," "More tension." These are about emotion. They’re gold. Act on them.

- Technical notes: "Use more cellos," "Less reverb," "Change the key." These are about tools. Ask why. Maybe they’re trying to say, "I need it to feel smaller."

- Personal preferences: "I hate strings." That’s not a note-it’s a history. Dig deeper. Maybe they had a bad experience with a previous composer. Or maybe they associate strings with bad TV dramas.

Always respond with: "Can you tell me what you’re feeling when you hear it?" That shifts the conversation from style to substance.

Real Examples from Real Films

Take Manchester by the Sea. The score is almost nonexistent. But the few moments of music-a lone piano, a single violin-hit like a punch. The director, Kenneth Lonergan, didn’t want music to "explain" the pain. He wanted it to be the space around the pain. The composer,Leslie Barber, used silence as an instrument. That’s collaboration.

Or Arrival. The score uses low-frequency tones that aren’t heard so much as felt. The director, Denis Villeneuve, told the composer, Jóhann Jóhannsson: "I want the music to sound like the aliens are breathing in the room." That’s not a technical request. It’s a sensory one. And it led to one of the most original scores of the decade.

What Happens When It All Comes Together

There’s a moment in every great film score when you realize the music wasn’t added-it was always there. The director didn’t tell you what to write. You just understood it. That’s the magic.

It’s not about being the best musician. It’s about being the best listener. The best collaborator. The one who can sit in silence with a director and know exactly when to play the next note.

When you get it right, the music doesn’t just support the film. It becomes part of its DNA. And no one-not even the director-can imagine it any other way.

How do I start a conversation with a director about music if they don’t know what they want?

Start by asking them to describe the emotion of a scene using senses other than sound. What does it smell like? What color is it? What texture does it have? These questions bypass technical language and get to the emotional core. Then play one short, bold idea-no options-and ask for a reaction.

Should I use temp music in my demos?

Only if you attach clear notes explaining why you chose it. Don’t just say "use this"-say "I picked this because the rhythm mirrors the character’s breathing pattern." Temp music is a tool, not a destination. The goal is to help the director understand the emotional direction, not to copy the track.

What if the director wants something cliché, like a swelling orchestral cue?

Don’t argue. Ask why. Often, they’re reaching for a feeling they can’t name-like hope, release, or triumph. Offer a variation: instead of a full orchestra, try a solo cello with a single synth pad underneath. Or use a choir singing vowels only, no words. Give them the emotion without the trope.

How do I know when to push back on feedback?

Push back only when the feedback contradicts the story’s emotional truth. If a director asks for a happy tune during a character’s death scene, ask: "Are we trying to make this feel lighter, or are we missing something in the performance?" Sometimes the real issue isn’t the music-it’s the edit or the acting. Your job is to help them see that.

What’s the biggest mistake composers make when working with directors?

Thinking their job is to make music. It’s not. Their job is to make the director feel understood. The best scores aren’t the most complex-they’re the ones that make the director say, "That’s exactly what I was hearing in my head."